Scientists Discover How Two Internal Skeletons Prevent Blockages in Developing Eggs

A careful study in fruit flies shows how two internal support systems inside cells work together during egg development, helping prevent blockages that can stop reproduction.

Egg development is often described in genetic or biochemical terms. But at its core, it is also a physical process. Cells must withstand pressure, shift large internal structures, and keep materials moving without clogging narrow passageways.

Inside developing eggs, this challenge becomes especially clear. If internal organization fails even briefly, development can stall completely.

To meet these demands, cells rely on internal scaffolding systems known as the cytoskeleton. Two major components dominate this system. One is actin, which forms thin filaments that can bundle into strong cables. The other is microtubules, thicker hollow tubes that span long distances inside the cell.

For many years, scientists studied these two systems separately. Actin was linked to shape and force. Microtubules were linked to transport and organization. Real cells, however, do not divide their labor so neatly.

A new study brings these systems together, examining how they coordinate during a crucial stage of egg development.

Why Fruit Flies Offer Clear Answers

The research focuses on the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster. Despite its small size, this insect has been a powerful model for understanding development.

Fruit fly ovaries are made up of repeated units called egg chambers. Each egg chamber contains 16 connected germ cells wrapped in a layer of support cells.

Only one of the 16 germ cells becomes the egg itself, known as the oocyte. The remaining 15 become nurse cells. Their role is to support the oocyte by producing RNA, proteins, and other materials.

These materials move into the oocyte through small openings called ring canals. At early stages, this transfer happens gradually. Later, it becomes fast and forceful.

This final transfer stage is where things can go wrong.

The Risk of Internal Blockage

Late in development, nurse cells empty most of their contents into the oocyte in a process called cytoplasmic dumping. The flow is rapid and intense.

Inside each nurse cell sits a large nucleus. If the nucleus drifts too close to a ring canal during dumping, it can block the opening like a cork in a bottle.

To prevent this, the nurse cells build thick actin cables before dumping begins. These cables grow from the outer edge of the cell toward the nucleus.

As they elongate, they push the nucleus away from the ring canals. This creates a clear path for cytoplasm to flow.

Previous studies showed that when actin cables fail to form, dumping often fails as well. Egg development then stops.

What remained unclear was how other internal structures respond to this process.

Microtubules Are Part of the Same Story

Microtubules fill the nurse cells alongside actin cables. They form networks in the cytoplasm and along the cell cortex.

Microtubules are best known for serving as tracks for motor proteins that carry cargo. They also help cells resist deformation.

A key feature of microtubules is that they can be chemically modified. One such modification is acetylation, which makes microtubules more stable and resistant to mechanical stress.

Because nurse cells experience increasing pressure before dumping, stabilized microtubules may be especially important at this stage.

The researchers wanted to know whether changes in actin cable formation affect microtubules, and if so, how.

Watching Development Step by Step

The team focused on a developmental window called stage 10B. This stage occurs just before dumping and can be divided into smaller substages.

By carefully staging egg chambers, the researchers tracked how internal structures changed over time.

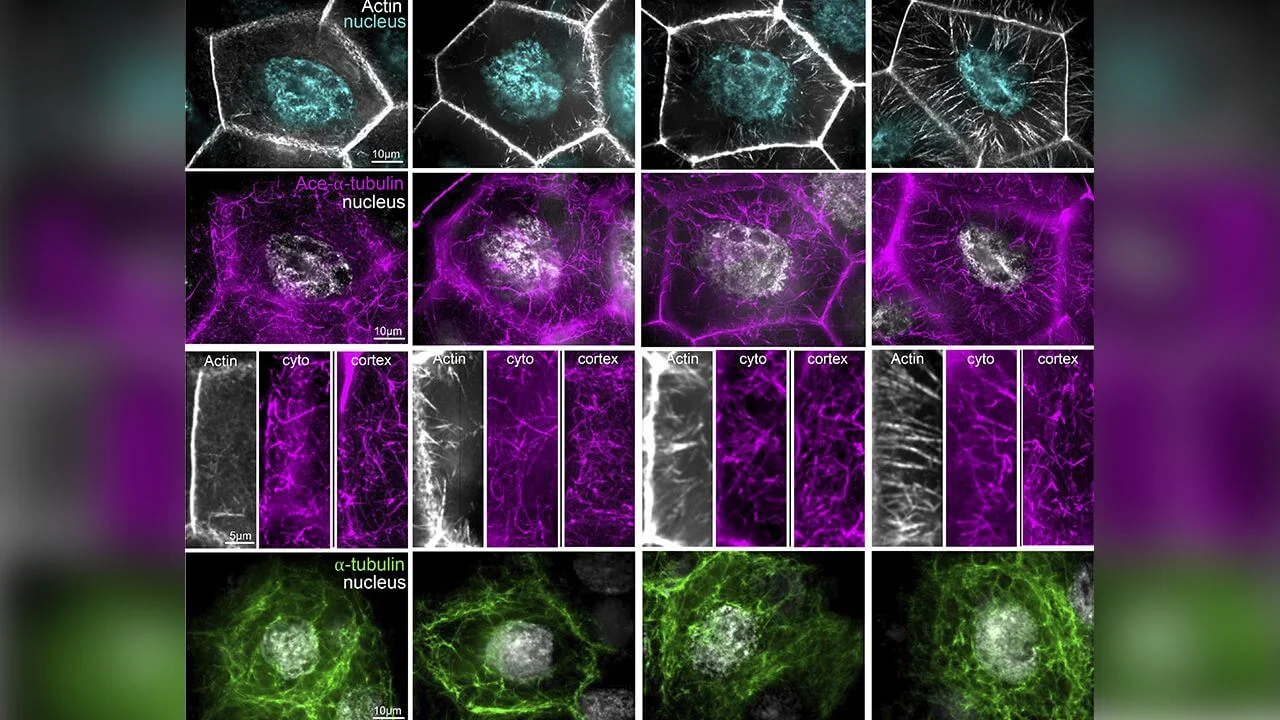

They labeled actin filaments, acetylated microtubules, and nuclei with fluorescent markers. This allowed them to see how these components behaved in the same cells.

As actin cables grew longer and denser, acetylated microtubules also became more abundant. The timing was striking.

Still, timing alone does not prove a connection. The next step was to interfere with actin directly.

Breaking Actin Reveals Unexpected Effects

To test whether actin influences microtubules, the researchers disrupted proteins that help build and bundle actin filaments.

These proteins included formins, Ena, Fascin, Quail, and Fimbrin. Each plays a role in shaping actin cables.

When these proteins were reduced, actin cables became fewer or shorter, just as expected.

What stood out was what happened to microtubules.

In some cases, the density of acetylated microtubules dropped. In others, the organization of microtubules near the cell cortex changed.

The effects were not identical across all conditions. Different actin disruptions led to different microtubule responses.

This variability suggested that microtubules were not simply following a single actin signal.

A Mechanical, Not Just Molecular, Connection

If actin and microtubules were linked by one specific protein, disrupting actin should have caused the same microtubule defect every time.

That did not happen.

Instead, the results pointed to a more indirect relationship. Actin cables appeared to change the physical environment inside the cell. Microtubules then adjusted to those changes.

As actin cables stiffened the cytoplasm and pushed against internal structures, microtubules likely experienced greater mechanical stress.

Acetylation is known to make microtubules more resistant to bending and breakage. The increase in acetylated microtubules during actin cable growth fits this idea.

In this view, actin does not instruct microtubules directly. It reshapes the space they occupy.

Changes at the Cell Cortex

Microtubules often originate from organizing centers marked by a protein called gamma-tubulin.

The study examined gamma-tubulin spots at the cell cortex during late stage 10B.

These spots became less common as development progressed. This suggests that the cell gradually reduces new microtubule growth from the cortex as dumping approaches.

Interestingly, this change occurred even when actin assembly was disrupted. That means some aspects of microtubule regulation follow their own developmental schedule.

Not all coordination depends on actin.

Shared Proteins, Limited Roles

Some proteins are known to interact with both actin and microtubules in other systems. These include spectraplakins and plus-end tracking proteins.

The researchers tested whether such proteins were essential for the observed coordination.

In several cases, removing these proteins did not disrupt the basic relationship between actin cables and microtubules.

This finding supports the idea that coordination can emerge from combined mechanical forces and spatial constraints, rather than relying on one molecular bridge.

Why These Findings Matter

At first glance, fruit fly egg cells may seem far removed from human biology. Yet the basic components involved are shared across animals.

Actin and microtubules are present in nearly all cells. Many tissues, including muscles, nerves, and epithelia, experience mechanical stress.

Problems in cytoskeletal coordination are linked to infertility, developmental disorders, and cancer.

By showing how coordination can arise naturally in a living tissue, this study adds an important piece to the puzzle.

It also highlights the limits of studying cytoskeletal systems in isolation.

What Remains Unknown

The study focused on a specific stage of egg development in one organism. Whether the same principles apply elsewhere remains an open question.

The signals that trigger increased microtubule acetylation during actin cable formation are not fully understood.

It is also unclear whether altering microtubules can compensate for defective actin cables.

These questions will likely guide future research.

Seeing the Cytoskeleton as a Whole

For a long time, actin and microtubules were treated as separate topics. This work reinforces the idea that they function as parts of a single system.

Inside cells, structure, force, and timing are deeply connected. Changes in one network ripple through the other.

By studying this interaction during a demanding developmental event, the researchers offer a clearer picture of how cells stay functional under pressure.

Egg development depends not on one internal skeleton, but on careful cooperation between two.

The research was published in Journal of Cell Biology on January 09, 2026.

This content has been reviewed by subject-matter experts to ensure scientific accuracy. Learn more about us and our editorial process.

Last reviewed on .

Article history

- Latest version

Reference(s)

- Chou, Wei-Chien., et al. “Developmentally regulated actin–microtubule cross talk in Drosophila oogenesis.” Journal of Cell Biology, 09 January 2026, doi: 10.1083/jcb.202411007. <https://rupress.org/jcb/article/225/3/e202411007/281372/Developmentally-regulated-actin-microtubule-cross>.

Cite this page:

- Posted by Elizabeth Taylor