Cells Have a Little-Known Cleanup Crew, and Scientists Just Found Its Missing Sensor

Cells rely on a little-known waste disposal pathway tied to the Golgi apparatus. A new study reveals how it selectively targets proteins, uncovering a molecular sensor with implications for cell health and disease.

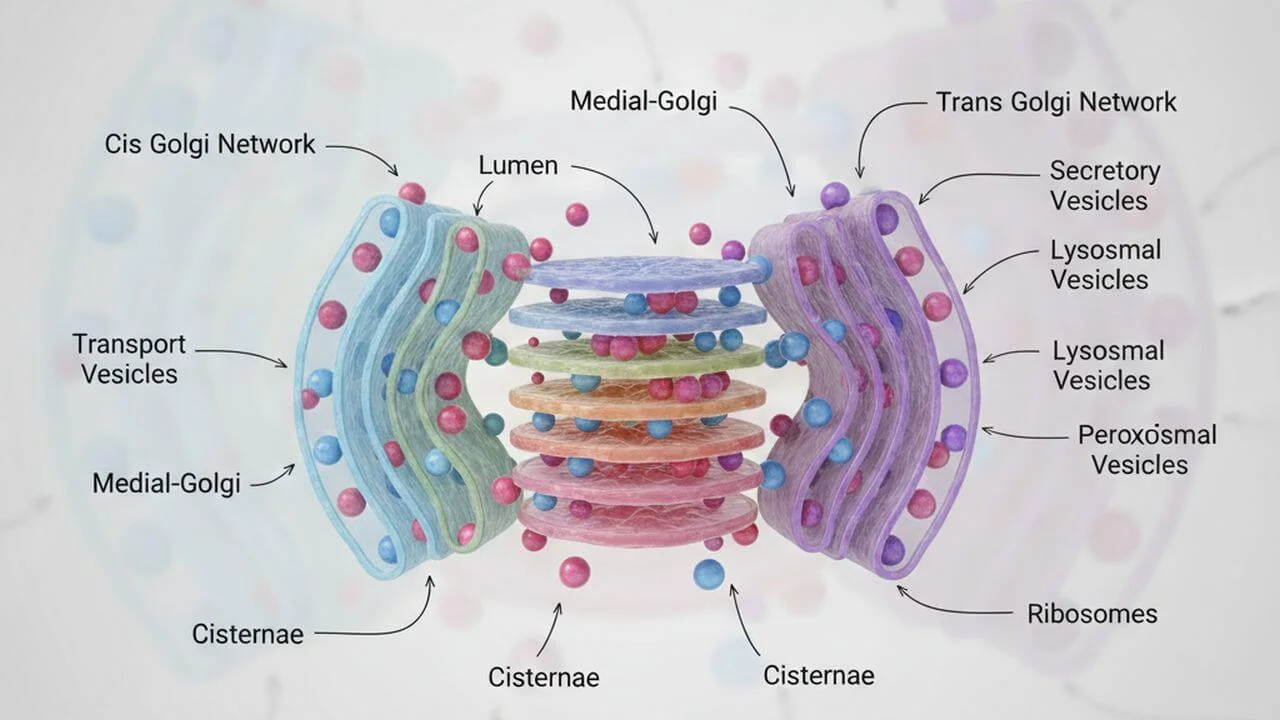

Every cell in your body runs like a miniature city. Proteins are manufactured, modified, shipped, and recycled with astonishing efficiency. One of the busiest hubs in this microscopic metropolis is the Golgi apparatus, a stack of membrane-bound compartments that acts like a postal center, sorting and dispatching proteins to their final destinations.

But what happens when something goes wrong? What if a protein passing through the Golgi is defective, unnecessary, or potentially harmful?

For decades, scientists have focused on two major cellular disposal systems. One is the proteasome, which chews up proteins marked for destruction. The other is autophagy, a process in which large cellular structures are engulfed and broken down in lysosomes. Both rely on molecular tags, often based on ubiquitin, a small protein that acts as a cellular “destroy me” label.

Yet cells also possess a lesser-known pathway that specifically handles proteins associated with the Golgi. It is called Golgi membrane-associated degradation, or GOMED. Although researchers have known about GOMED for years, one central mystery has lingered. How does this system decide which proteins to destroy?

A new study published in Nature Communications finally provides an answer.

A cleanup pathway hiding in plain sight

GOMED looks deceptively similar to autophagy. Under the microscope, it forms double-membrane structures that eventually fuse with lysosomes, where proteins are degraded. But despite these visual similarities, GOMED is fundamentally different.

Autophagy can target damaged mitochondria, invading microbes, or aggregated proteins throughout the cell. GOMED, by contrast, focuses on proteins that have passed through the trans-Golgi network, especially secreted proteins and membrane proteins that are en route to the cell surface.

Previous research had shown that GOMED becomes active under conditions of cellular stress, such as DNA damage or disruptions in protein trafficking. It also plays a critical role during certain developmental processes, including the final maturation of red blood cells, where mitochondria must be removed before the cells enter circulation.

What remained unknown was how GOMED recognizes its cargo. Autophagy uses a suite of adaptor proteins that bind ubiquitin tags on unwanted material. Whether GOMED relied on similar adaptors, or on an entirely different strategy, was an open question.

A surprising suspect: optineurin

The new study set out to identify the molecular players that guide proteins into the GOMED pathway. The researchers focused on adaptor proteins already known from autophagy, including p62, NDP52, NBR1, TAX1BP1, and optineurin.

Among these candidates, one stood out.

Optineurin, often abbreviated as OPTN, is a protein previously linked to selective autophagy and to neurological diseases such as glaucoma and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. It was known to bind ubiquitinated cargo and help shuttle it toward degradation pathways. But its role in GOMED had not been established.

By triggering GOMED in cells while disabling conventional autophagy, the researchers observed something striking. When optineurin was removed, GOMED activity dropped sharply. Other adaptor proteins had little effect.

In other words, optineurin was not just involved. It appeared to be essential.

Following the trail to the Golgi

To confirm optineurin’s role, the team tracked where it traveled inside stressed cells. Under normal conditions, optineurin is distributed throughout the cytoplasm. But when GOMED was activated, optineurin accumulated at the trans-Golgi membranes, precisely where GOMED structures originate.

Later, optineurin-containing structures were seen merging with lysosomes, the acidic compartments where cellular waste is destroyed. This spatial choreography suggested that optineurin acts as a bridge, linking unwanted Golgi-associated proteins to the degradation machinery.

The effect was specific. When cells lacked optineurin, GOMED structures failed to form properly, even though autophagy remained functional. This distinction underscored that GOMED is not simply a variant of autophagy, but a parallel system with its own molecular logic.

The key signal: an unusual ubiquitin chain

Identifying the adaptor was only half the puzzle. The next question was what kind of molecular tag optineurin recognizes during GOMED.

Ubiquitin tagging is more complex than it may seem. Ubiquitin molecules can link together in different ways, forming chains with distinct shapes and meanings. Some chains, such as K48-linked ubiquitin, signal proteins for destruction by the proteasome. Others, like K63-linked chains, are commonly used in autophagy.

The researchers tested a wide range of ubiquitin linkages to see which ones appeared on GOMED substrates. The answer was unexpected.

GOMED relies heavily on K33-linked polyubiquitin chains.

These chains are relatively rare and have been poorly understood compared to their more famous counterparts. In this study, proteins destined for GOMED were selectively tagged with K33-linked ubiquitin. Optineurin bound strongly to these tags, capturing the proteins and directing them into Golgi-derived degradation structures.

When the researchers interfered with K33 ubiquitination, GOMED efficiency dropped. When they increased K33-linked tags, GOMED activity surged.

This discovery effectively identifies a third major ubiquitin-based degradation signal, alongside the classical pathways used by the proteasome and autophagy.

A molecular handshake built for precision

Why optineurin and K33-linked ubiquitin work so well together comes down to protein structure. Optineurin contains multiple domains capable of interacting with ubiquitin, but the study revealed that one region, a zinc-finger domain, is especially important for GOMED.

When this domain was removed or disrupted, optineurin could no longer bind ubiquitinated cargo effectively, and GOMED stalled. Interestingly, other ubiquitin-binding regions of optineurin, previously associated with autophagy, were not essential in this context.

This finding highlights how cells reuse molecular components in different ways, fine-tuning their interactions depending on the pathway involved.

From artificial cargo to real cellular proteins

To ensure their findings were not limited to experimental constructs, the researchers examined naturally occurring GOMED substrates.

One such protein is integrin alpha-5, a cell surface receptor involved in cell adhesion and signaling. Integrin alpha-5 passes through the Golgi on its way to the plasma membrane, making it an ideal candidate for GOMED.

Under conditions that activate GOMED, integrin alpha-5 accumulated inside cells and was delivered to lysosomes. This process depended on optineurin and K33-linked ubiquitin, and it occurred independently of classical autophagy.

Another endogenous substrate, mesothelin, followed the same pattern. Together, these examples demonstrate that the optineurin-K33 pathway is not an experimental artifact, but a genuine cellular mechanism used to manage real proteins.

Cleaning house during red blood cell maturation

Perhaps the most striking demonstration of GOMED’s importance came from experiments in living animals.

As red blood cells mature, they undergo a dramatic transformation. They eject their nucleus and eliminate mitochondria, becoming streamlined oxygen carriers. Previous work had shown that this mitochondrial clearance depends on GOMED rather than autophagy.

In mice lacking optineurin, this process went awry. Mature red blood cells retained mitochondria, an abnormal state associated with distorted cell shape and impaired function. The results confirmed that optineurin-mediated GOMED is essential for mitochondrial removal during erythrocyte maturation.

This in vivo evidence cements GOMED as a biologically significant pathway, not just a curiosity observed in cultured cells.

Why this discovery matters

At first glance, the details of ubiquitin chains and adaptor proteins may seem esoteric. But understanding how cells decide what to destroy has profound implications.

Failures in protein quality control are linked to neurodegenerative diseases, cancer, immune disorders, and aging. Optineurin itself has already been implicated in several neurological conditions. By revealing a new pathway in which optineurin operates, the study opens fresh avenues for understanding how its dysfunction might contribute to disease.

The discovery of K33-linked ubiquitin as a degradation signal also expands the language of cellular signaling. Cells do not rely on a single “destroy me” tag, but on a rich vocabulary of molecular codes, each directing cargo to a specific fate.

A broader view of cellular order

Cells are often described as chaotic, bustling environments. Yet discoveries like this one reveal an underlying order, a carefully regulated network of decisions about what to keep and what to discard.

GOMED, once a poorly understood process on the fringes of cell biology, now emerges as a selective, tightly controlled pathway with its own adaptor protein and its own ubiquitin signature.

As researchers continue to map these hidden systems, they are not just filling gaps in textbooks. They are uncovering the fundamental logic that keeps cells alive, adaptable, and resilient.

The research was published in Nature Communications on October 20, 2025.

This article has been fact checked for accuracy, with information verified against reputable sources. Learn more about us and our editorial process.

Last reviewed on .

Article history

- Latest version

- Last updated by Dayyal Dungrela, MLT, BSc, BS

Reference(s)

- Nibe-Shirakihara, Yoichi., et al. “Optineurin is an adaptor protein for ubiquitinated substrates in Golgi membrane-associated degradation.” Nature Communications, vol. 16, no. 1, 20 October 2025, doi: 10.1038/s41467-025-64400-3. <https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-64400-3>.

Cite this page:

- Posted by Chetan Prem