In a Lab on Earth, Scientists Tested Whether Life Could Still Build on Mars

Mars soil is chemically hostile to life, yet a laboratory study shows some bacteria can survive its toxicity and still bind soil together, though only weakly and under strain.

Mars looks dry, quiet, and empty. Its surface stretches out in wide plains of reddish dust, broken rock, and fine sand. From a distance, it resembles deserts on Earth.

Up close, the similarity fades.

Mars soil carries perchlorate salts, chemicals that are harmless to machines but deeply hostile to life. These salts interfere with basic cellular processes, damaging proteins and breaking down membranes. Even small amounts can be toxic.

NASA missions have shown that perchlorates are not rare contaminants. They are spread across the planet, mixed directly into the soil future astronauts would have to live on, farm, and build with.

That reality forces an uncomfortable question. If humans want to stay on Mars, can anything alive actually work there?

A Hopeful Idea Rooted in Bacteria

For years, engineers and biologists have been exploring a simple idea. Instead of hauling bricks from Earth, why not grow them on Mars?

Some bacteria naturally glue soil together. On Earth, they do this quietly underground. They consume urea, change their surroundings, and trigger the formation of calcium carbonate, the same mineral found in limestone.

This process, known as microbially induced calcite precipitation, slowly turns loose grains into solid material. In laboratories, it has been used to repair concrete and stabilize soil.

Mars soil is rich in minerals. In theory, bacteria could turn that dust into shelter walls.

But perchlorates stand in the way.

Searching for a Tough Microbe

The search for a suitable bacterium began in an ordinary place. In March 2021, researchers collected soil from Bangalore, India.

Back in the lab, they encouraged bacteria from the soil to grow in a solution containing urea. This setup favors microbes capable of producing mineral cement.

Several strains appeared. One performed noticeably better than the rest.

This bacterium showed strong urease activity and produced visible mineral deposits. Genetic analysis revealed it was closely related to Sporosarcina pasteurii, a species already known for its biocement abilities.

The researchers gave it a name tied to its origin, SI_IISc_isolate.

Its genome told a promising story. Alongside genes responsible for mineral formation were genes linked to perchlorate reduction, hinting that this microbe might tolerate Martian chemistry better than most.

Introducing the Toxic Challenge

The next step was simple but unforgiving.

The researchers exposed the bacteria to magnesium perchlorate, gradually increasing the concentration. The levels chosen mirrored what has been measured on Mars, ranging from 0.5 percent to 3 percent.

At first, the bacteria grew slowly but steadily. As perchlorate levels rose, growth faltered.

At 3 percent perchlorate, growth stopped entirely. This concentration marked a clear biological limit.

Below that threshold, some cells survived. But survival came at a cost.

Stress Shows in Shape and Size

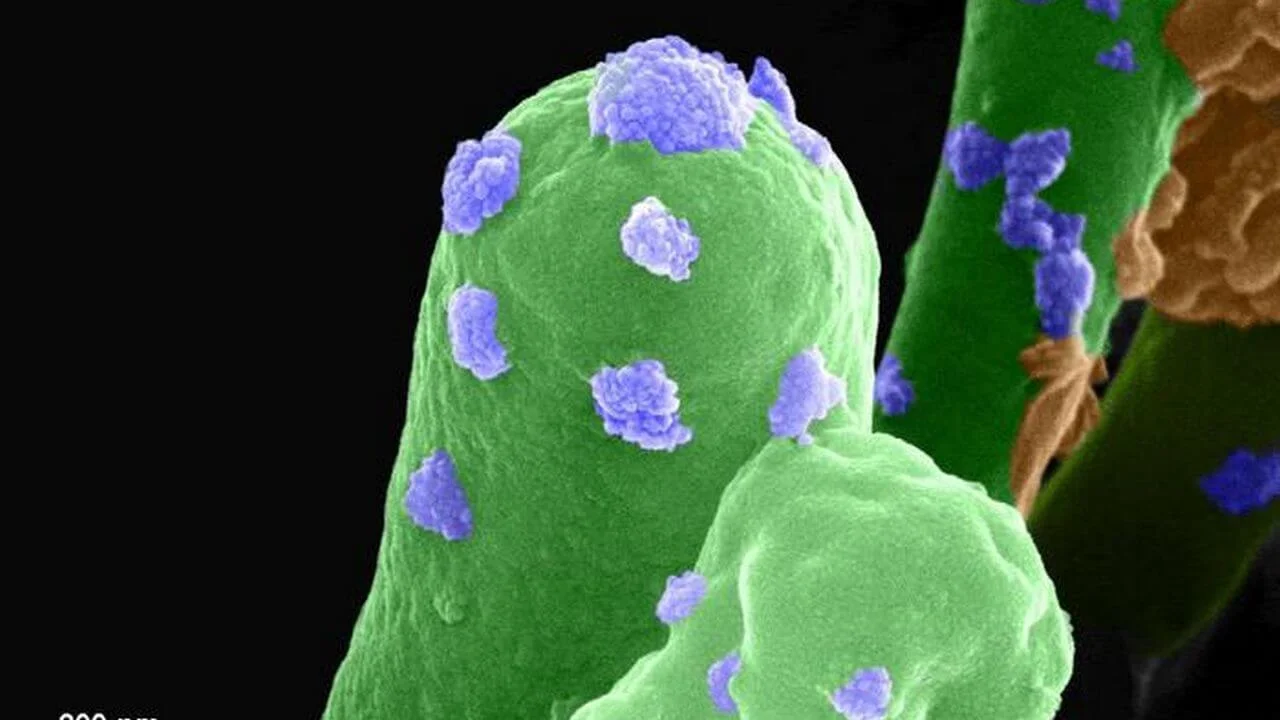

Under the microscope, the bacteria looked different.

Cells exposed to perchlorate shrank in size. Many died within hours. Live and dead staining showed a clear pattern. The higher the perchlorate concentration, the fewer living cells remained.

Still, a fraction of the population endured.

This mattered. It showed that perchlorate does not wipe out life instantly. Instead, it pushes organisms into a state of constant stress.

An Unusual Way to Stay Alive

As stress increased, something unexpected happened.

The bacteria began releasing thick layers of extracellular material. This sticky substance wrapped around cells and connected them into clusters.

Instead of living as separate individuals, the bacteria grouped together.

The researchers described this as multicellularity-like behavior. It was not true multicellular life, but it looked like cooperation under pressure.

Similar behavior has been seen in bacteria facing salt, heat, or heavy metals. On Mars-like soil, perchlorate appeared to trigger the same response.

Clustering may help bacteria share resources and shield one another from chemical harm.

Building Minerals Under Stress

Survival alone was not the goal. The bacteria still needed to perform their key task.

Even under perchlorate exposure, the microbes continued producing calcium carbonate. The amount decreased as toxicity increased, but it never dropped to zero.

X-ray analysis confirmed that the minerals were mostly calcite, with small amounts of related crystal forms. Electron microscopy showed bacterial cells embedded directly within the mineral structures they created.

The bacteria were stressed, slowed, and damaged, but they were still building.

A Test Using Mars-Like Soil

To move beyond petri dishes, the researchers turned to Mars Global Simulant-1. This artificial soil closely matches the grain size and mineral makeup of real Martian regolith.

They mixed the simulant with bacteria, nutrients, and 1 percent perchlorate. The mixture was poured into small cube molds.

For five days, the bacteria were left to work.

As water evaporated and minerals formed, the loose soil slowly hardened.

The Bricks Told a Cautious Story

Once dried, the cubes were tested for strength.

They were real bricks, but fragile ones.

Bricks made in the presence of perchlorate showed very low compressive strength, around 0.064 megapascals. Some cracked under light pressure. Others crumbled.

Even bricks made without perchlorate were weak, though slightly stronger.

The message was clear. Biology alone struggles to build under Martian chemistry.

A Small Boost From a Simple Additive

The researchers tried one more adjustment.

They added guar gum, a natural plant-based adhesive often used in food and industry.

With guar gum mixed in, brick strength improved noticeably. The material helped bind particles together, supporting the weakened bacterial cement.

This suggested that future construction on Mars may rely on combined approaches, where biology does part of the work and simple additives do the rest.

What the Study Really Shows

This research does not promise cities grown from bacteria on Mars.

Instead, it shows something more grounded.

Life can function in Martian soil chemistry, but only barely. It adapts, clusters, and survives, yet its abilities are sharply limited.

For astrobiology, the findings offer insight into how life might persist under chemical stress. For space exploration, they outline the boundaries of biological construction.

The Limits Still Loom Large

All experiments were done under Earth conditions. Mars is colder, drier, bombarded by radiation, and shaped by lower gravity.

Each of these factors could further restrict bacterial survival.

Whether microbes could adapt over longer timescales or be engineered to tolerate perchlorates better remains an open question.

A Quiet Lesson From a Difficult Planet

Mars does not easily welcome life.

This study shows that even the simplest biological tasks become difficult when chemistry turns hostile. Yet it also shows that life rarely gives up immediately.

Under pressure, it adapts, cooperates, and keeps going, even when the results are modest.

That quiet resilience may matter more than bold promises as humans plan their future beyond Earth.

The research was published in PLOS One on January 29, 2025.

This content has been reviewed by subject-matter experts to ensure scientific accuracy. Learn more about us and our editorial process.

Last reviewed on .

Article history

- Latest version

Reference(s)

- Dubey, Swati., et al. “Effect of perchlorate on biocementation capable bacteria and Martian bricks.” PLOS One, 29 January 2026, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0340252. <https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0340252>.

Cite this page:

- Posted by Elizabeth Taylor