Bacterial Toxins Can Trigger Prion Like Brain Damage, Study Finds

Chronic bacterial toxins and synthetic misfolded prion proteins can independently damage the brain and accelerate classical prion disease. This suggests hidden neurodegenerative pathways that operate even without typical prion markers.

Brain disorders that involve misfolded proteins continue to puzzle scientists because the same types of protein abnormalities appear in conditions as different as prion disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and some forms of Parkinson’s disease. A central question has persisted for years. Does the harmful activity begin only after large, detectable aggregates appear in the brain, or can earlier and smaller protein changes quietly start the damage long before classic markers become visible?

A new study offers a significant clue. Researchers found that chronic exposure to bacterial lipopolysaccharide, a common molecule released during infections, and a recombinant prion protein altered by the same bacterial toxin, can each produce progressive brain injury in healthy mice. These harmful effects emerged even when no classical protease resistant prion protein was detectable. The findings show that inflammation, altered protein shapes, and infectious prions may converge on similar damaging pathways inside the brain.

The implications reach far beyond prion biology, since chronic low grade inflammation and subtle protein misfolding are increasingly linked to a wide range of neurodegenerative conditions.

The Scientific Problem

Prion diseases have been defined traditionally by the presence of a misfolded, protease resistant form of prion protein, often called PrPSc. This form accumulates in the brain, produces spongiform damage, and can transmit disease between individuals. However, scientists have struggled to understand whether toxicity requires PrPSc itself or whether smaller misfolded fragments and intermediate shapes might be harmful on their own.

At the same time, accumulating evidence suggests that chronic inflammation can disturb protein folding pathways and weaken the brain’s defenses. Lipopolysaccharide, a major component of bacterial outer membranes, is known to provoke strong immune activation. Earlier laboratory work showed that LPS can partially convert recombinant prion protein into a misfolded form in vitro, but it was unclear whether such altered proteins could induce disease in living organisms.

The study addressed three important gaps.

- Can LPS converted recombinant prion protein damage the brains of normal mice?

- Can chronic LPS exposure alone initiate harmful changes in brain tissue?

- How does chronic inflammation influence the progression of classical infectious prion disease?

How the Researchers Approached the Study

The scientists used female FVB/N mice and assigned them to six carefully controlled groups. Each group received one of the following: saline, chronic low dose LPS, recombinant LPS converted mouse prion protein, the same recombinant protein combined with chronic LPS, classical RML prions, or RML prions combined with chronic LPS.

LPS or saline was delivered continuously for six weeks using small osmotic pumps implanted under the skin. The recombinant misfolded protein and infectious prions were injected subcutaneously at the time of pump placement. This design was chosen because it models a realistic peripheral route that resembles how animals encounter bacterial toxins or infectious agents in the real world.

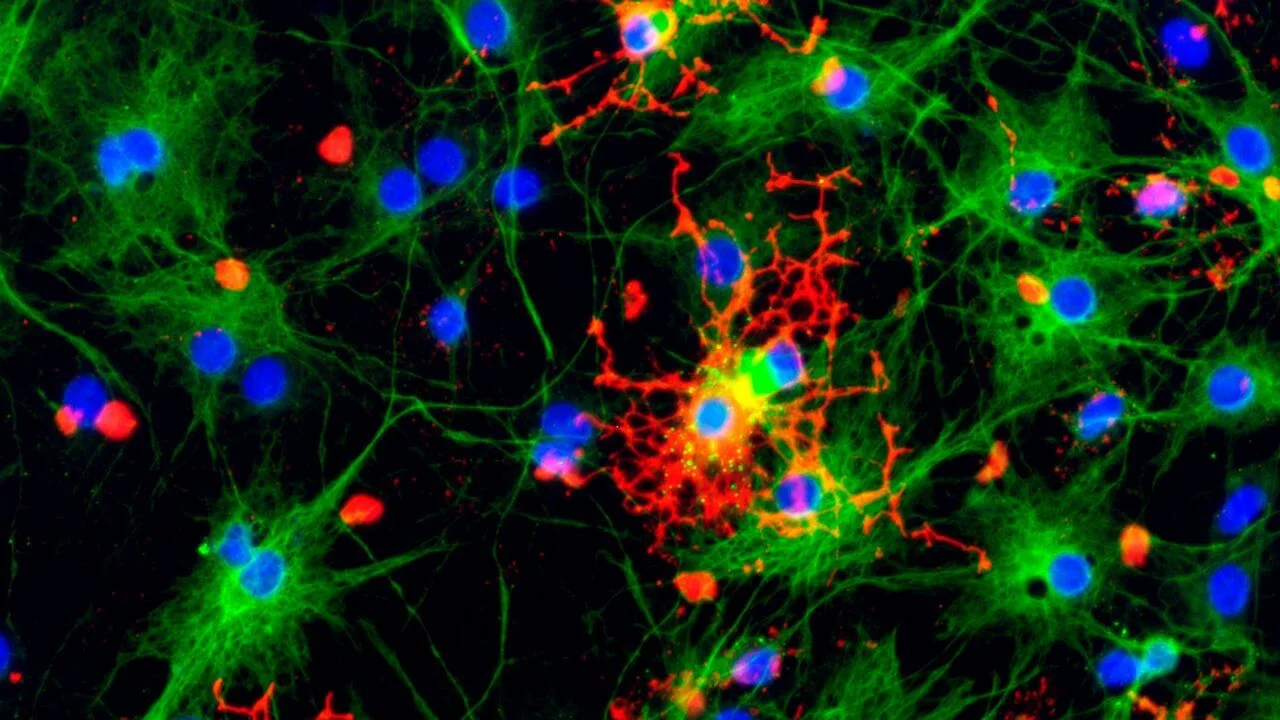

The researchers monitored the mice for weight changes, survival, behavior, and clinical signs for up to 750 days, which allowed them to observe slow progressing neurological injury. Brain tissues were examined using detailed histology, immunohistochemistry, Western blotting, and cell based infectivity assays to look for classical prion features such as protease resistant PrPSc.

This multi layered strategy provided a clear way to compare inflammation driven damage, recombinant protein driven damage, and infectious prion replication.

The Breakthrough Findings

1. Recombinant LPS converted prion protein caused brain damage without classical PrPSc

Mice that received the recombinant prion protein developed clear spongiform changes and strong astrogliosis in several regions of the brain. However, none of the methods used by the researchers detected classical PrPSc in these animals. This showed that misfolded prion protein that lacks the usual protease resistant signature can still inflict long term injury. The damage progressed slowly over many months, indicating a toxic process independent of infectious prion replication.

2. Chronic LPS alone produced neurodegeneration and amyloid deposits

Mice exposed to continuous low dose LPS without any prion protein also developed brain pathology. Cerebellar vacuolation was prominent, and amyloid beta deposition appeared in multiple regions. About forty percent of these mice eventually died. This finding demonstrates that sustained low level inflammation alone can trigger progressive brain injury and protein accumulation similar to early features seen in aging or Alzheimer’s disease.

3. LPS accelerated infectious prion disease

When mice received both classical RML prions and chronic LPS exposure, disease onset occurred significantly earlier. These mice accumulated more PrPSc in their spleens and brains and they reached the terminal stage of prion disease faster than mice infected with RML alone. This supports the idea that systemic inflammation amplifies prion replication and increases vulnerability of nervous tissue.

4. Combining recombinant prion protein with LPS produced mixed outcomes

The group that received both recombinant misfolded protein and chronic LPS showed variable results. Some mice displayed intense vacuolation and gliosis, while others showed moderate injury. As with the recombinant protein alone, no classical PrPSc was detected. The findings suggest that although chronic inflammation can influence the severity of damage, it does not convert the noninfectious recombinant protein into a classical prion agent in this model.

Why These Findings Matter

A broader view of neurotoxicity

The results challenge the long standing belief that protease resistant PrPSc is the only harmful agent in prion biology. Instead, smaller or more subtle misfolded shapes may be toxic before visible aggregates form. This mirrors ideas emerging in Alzheimer’s disease research, where soluble oligomers are now considered major drivers of early neural damage.

Inflammation as a key factor in neurodegeneration

The study demonstrates that chronic systemic inflammation is not a passive background event. It actively reshapes brain chemistry, encourages protein misfolding, and weakens protective barriers. Many common conditions, including metabolic syndrome and chronic infections, can produce low grade endotoxemia. The findings suggest that these conditions may quietly accelerate neurodegenerative processes.

Lessons for infectious prion disease

The observation that LPS accelerated RML disease progression has important implications. It suggests that environmental or medical conditions that increase inflammation could influence the severity or timing of prion illnesses. Understanding this relationship could aid in developing preventive or therapeutic strategies.

Potential therapeutic directions

If early misfolded intermediates are harmful, therapies that stabilize native prion protein or enhance the clearance of small misfolded species may be valuable. Since chronic endotoxemia appears destructive on its own, interventions that improve gut barrier function or reduce systemic inflammation may also offer new paths to prevention.

Caveats and Future Research

Although the study used extensive methods, some misfolded prion species may escape standard detection techniques. More sensitive biochemical tools will be required to characterize early toxic intermediates. Additionally, the findings come from a single mouse strain and specific exposure conditions. Future work should test other prion strains, genetic backgrounds, and patterns of inflammation.

Mechanistic studies are also needed to map the exact cellular pathways linking LPS, misfolded protein structures, and neuronal injury. Microglial activation, inflammatory signaling pathways, and synaptic vulnerability are promising targets for follow up research.

Conclusion

This study reveals that chronic bacterial toxins and a lab made misfolded prion protein can each damage the brain of healthy animals, even when the usual hallmarks of prion infection are absent. Classical infectious prions remain highly destructive, yet they are only one route to neurodegeneration. Inflammation, subtle protein misfolding, and noninfectious prion conformers can contribute to similar patterns of injury.

These insights broaden our understanding of how neurodegenerative diseases may begin and progress. They underscore the need to investigate early misfolded protein states and chronic inflammatory signals as potential drivers of long term brain decline. The findings open the door to new approaches that target protein stability, immune balance, and the earliest molecular events that shape brain health.

The research was published in the International Journal of Molecular Sciences on June 28, 2025.

This article has been fact checked for accuracy, with information verified against reputable sources. Learn more about us and our editorial process.

Last reviewed on .

Article history

- Latest version

- Last updated by Dayyal Dungrela, MLT, BSc, BS

Reference(s)

- Goldansaz, Seyed Ali., et al. “Lipopolysaccharide and Recombinant Prion Protein Induce Distinct Neurodegenerative Pathologies in FVB/N Mice.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, vol. 26, no. 13, 28 June 2025, doi: 10.3390/ijms26136245. <https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/26/13/6245>.

Cite this page:

- Posted by Chetan Prem