Bright Streaks on Mercury Hint the Planet Is Still Slowly Changing

Thin bright streaks on Mercury’s steep slopes may be signs of ongoing material loss beneath the surface. A global study suggests the planet is still quietly evolving today.

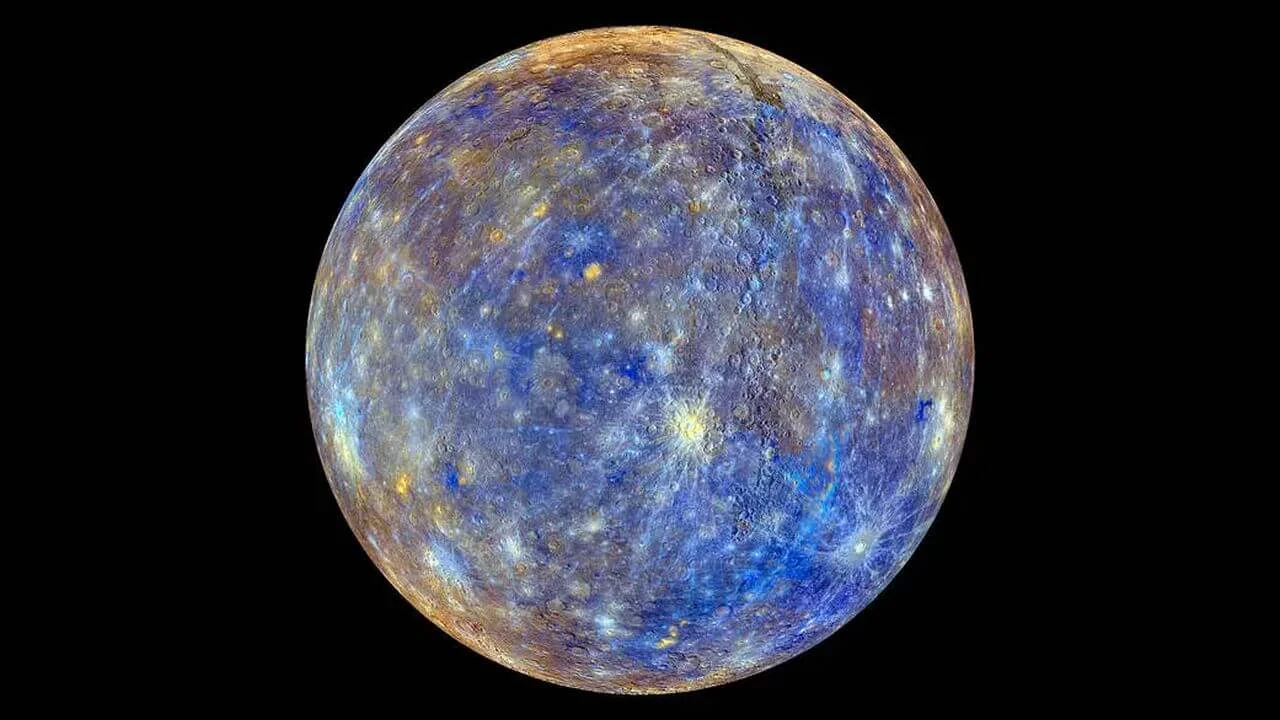

Mercury sits closest to the Sun, small and battered, with a surface shaped by extreme heat and ancient impacts. Daytime temperatures can rise above 700 kelvin, while nights turn sharply cold.

For a long time, scientists thought Mercury’s story was mostly over. Its surface looked old, heavily cratered, and frozen in time since the early days of the Solar System.

That view began to change after NASA’s MESSENGER spacecraft entered orbit in 2011. The mission returned thousands of detailed images that revealed landforms that did not quite fit the picture of a dead world.

Among them were strange, bright features etched into steep slopes. They looked fresh, thin, and oddly delicate.

The Curious Case of Slope Lineae

These features are known as slope lineae. They appear as narrow, bright streaks running downhill on crater walls, scarps, and ridges.

Some stretch for hundreds of meters. Others extend for several kilometers, tracing gentle curves along the terrain.

They are not thick deposits. They cast no shadows, which tells scientists they are very shallow, perhaps only a few meters deep.

Their sharp edges and high brightness suggest youth. On Mercury, surfaces usually darken and blur with time due to constant micrometeoroid impacts.

So when something looks crisp, it likely formed recently, at least in geological terms.

From Isolated Sightings to a Global Map

Before this study, slope lineae were known only from scattered reports. No one had looked for them across the entire planet.

The research team changed that by using artificial intelligence. They trained a deep learning system to scan thousands of MESSENGER images and flag features that matched the shape and brightness of slope lineae.

Each detection was then checked by hand. False signals were removed. Duplicates were merged.

In the end, the team identified 402 confirmed slope lineae. It was the first complete global catalog of these features.

Where the Streaks Appear Most Often

The lineae are not spread evenly across Mercury. Most appear in the northern hemisphere, where MESSENGER collected the clearest images.

Large clusters show up in smooth volcanic plains such as Budh Planitia and Sobkou Planitia. Others appear near Caloris Planitia, one of Mercury’s largest impact basins.

One crater stands out in particular. Degas crater contains the highest number of slope lineae found anywhere on the planet.

When researchers corrected for image quality, they noticed a clear trend. Better images reveal more lineae. This means many more may exist in poorly imaged regions, especially in the south.

A Strong Link to Impact Craters

Almost all slope lineae are tied to impact craters. About 90 percent are found inside crater walls rather than on open plains.

The host craters are usually small and relatively young. Their median diameter is around 10 kilometers.

These craters are large enough to dig into the subsurface and steep enough to create unstable slopes. Older, eroded craters rarely host lineae.

This pattern suggests slope lineae do not last forever. They likely fade or disappear as the surface ages.

Starting Points Near the Top

Most slope lineae begin near the top of a slope. Their starting points are often tiny bright patches that are difficult to resolve clearly.

In many cases, these patches resemble hollows. Hollows are shallow depressions found across Mercury and are thought to form when volatile materials escape from the surface.

About 87 percent of lineae start near hollow-like features. This close relationship hints at a shared origin.

It also suggests that slope lineae may simply be another way Mercury expresses the same underlying process.

Color Clues From Space

Where color data are available, slope lineae show a blue spectral slope. This means they reflect more light at shorter wavelengths.

Hollows show the same behavior. The surrounding terrain, by contrast, appears redder.

This similarity matters. It suggests the lineae are not just dust sliding downhill. Instead, they expose or deposit material that is chemically different from the background surface.

That difference points toward volatile-rich substances.

Steep Slopes and Sunlight

Slope lineae prefer steep terrain. Many occur on slopes approaching 35 degrees.

Dry rocky material should remain stable at these angles, which implies something is helping it move.

Orientation also plays a role. Most lineae face toward the equator, where sunlight is stronger and more consistent.

Interestingly, they do not cluster at Mercury’s hottest longitudes. This means heat alone is not the only factor.

Still, sunlight appears to be part of the story.

Temperature Patterns Beneath the Surface

The researchers compared thermal models of Mercury’s surface with lineae locations.

They found that lineae tend to occur in areas with slightly higher peak temperatures and larger temperature swings near the surface and at depths of about one meter.

The differences are subtle. They sit near the edge of statistical significance.

Even so, the pattern fits the idea that heat helps trigger or sustain the process that forms lineae.

At depths of two meters, the temperature signal disappears. This suggests the action happens close to the surface.

The Role of Ancient Lava Plains

More than half of all slope lineae are found in smooth plains created by ancient volcanic eruptions.

These plains likely act as a protective cap, sealing volatile-rich layers underneath.

When an impact breaks through this cap, it exposes the buried layer. Steep crater walls then provide a path for material to move downslope.

This layered structure seems important. Many sun-facing slopes lack lineae, which shows that sunlight and slope are not enough by themselves.

The presence of volatile-rich material beneath a cap appears to be essential.

What Does Not Seem to Matter

The study also tested other possible explanations.

Tectonic features, such as lobate scarps formed by Mercury’s shrinking interior, show little connection to slope lineae.

Volcanic vents overlap with some lineae clusters, but most lineae are far from known vents.

Fresh impact craters formed during the MESSENGER mission do not show new lineae nearby. This makes impacts an unlikely direct trigger.

No Visible Changes Yet

The team compared images of the same locations taken up to four years apart.

They saw no clear changes in the size, shape, or brightness of slope lineae.

This does not mean nothing is happening. It simply means the process is slow or happens at scales too small for MESSENGER to detect.

Even steady, tiny changes could keep the features looking fresh.

The Case for Volatile Loss

All lines of evidence point toward one main process. Mercury appears to be losing volatile materials from near its surface.

Sulfur is the leading candidate. Mercury is unusually rich in sulfur, and sulfur can sublimate at temperatures found on sunlit slopes.

As sulfur escapes, it may weaken surrounding material. This could allow thin layers to creep downhill, forming bright streaks.

Other volatiles are possible, but sulfur fits best with what is known about Mercury’s composition.

A Very Slow Process

Measurements suggest hollow growth is extremely slow when viewed sideways, perhaps centimeters over tens of thousands of years.

Vertical sulfur loss, however, could occur much faster under the right conditions.

This combination explains why slope lineae look young but do not visibly change over a few years.

Mercury may be reshaping itself quietly, grain by grain.

Why These Streaks Matter

Slope lineae may be one of the best signs of ongoing activity on Mercury.

They form on slopes where even small changes leave visible traces.

By studying them, scientists gain insight into Mercury’s interior, its chemistry, and its long-term evolution.

They also challenge the idea that small rocky planets stop changing early in their history.

What BepiColombo May Reveal

The joint ESA and JAXA BepiColombo mission is on its way to Mercury and will begin full science operations in late 2026.

It will provide sharper images, better coverage, and a longer time baseline than MESSENGER.

Scientists will be able to revisit known slope lineae and search for new ones.

If subtle changes are happening, BepiColombo may finally catch them in the act.

A Quietly Active World

Mercury does not have flowing water or erupting volcanoes today. It remains a harsh and silent place.

Yet these faint bright streaks suggest the planet is not completely still.

Beneath the surface, volatile materials may still be escaping, slowly altering the landscape.

Even the smallest planet, it seems, has not finished telling its story.

The research was published in Communications Earth & Environment on January 27, 2026.

This content has been reviewed by subject-matter experts to ensure scientific accuracy. Learn more about us and our editorial process.

Last reviewed on .

Article history

- Latest version

- Peer reviewed by Dr. Arjun Patel, PhD

Reference(s)

- Bickel, V. T.., et al. “Slope lineae as potential indicators of recent volatile loss on Mercury.” Communications Earth & Environment, vol. 7, no. 1, 27 January 2026, doi: 10.1038/s43247-025-03146-8. <https://www.nature.com/articles/s43247-025-03146-8>.

Cite this page:

- Posted by Aisha Ahmed