Astronomers Identify the Largest Sulfur-Bearing Ring Molecule in Interstellar Space

Scientists have spotted an unusually large sulfur-containing ring molecule inside a dense cloud near the Milky Way’s center, giving new clues about how complex chemistry may develop long before planets or life appear.

Sulfur plays a quiet but crucial role in life on Earth. It helps proteins fold properly, supports enzyme activity, and appears in essential amino acids. Without sulfur, biology as we know it would not function.

Yet when astronomers look into space, sulfur often seems to be missing.

Models of interstellar chemistry predict that sulfur should be common inside molecular clouds, the cold regions where stars and planets eventually form. But telescope observations usually detect far less sulfur than expected. This mismatch has puzzled scientists for years and is often called the sulfur depletion problem.

A new discovery now offers a partial answer.

A Chemical Discovery Near the Galactic Center

The newly detected molecule was found in a molecular cloud named G+0.693–0.027. This cloud sits close to the center of the Milky Way, roughly 25,000 light-years from Earth.

The Galactic Center is not a calm place. Gas clouds there are warmer, denser, and more frequently disturbed by shock waves and radiation. These harsh conditions may sound destructive, but they can also drive unusual chemical reactions.

Because of this, G+0.693–0.027 has become a favorite target for astrochemists. Over the years, it has revealed many complex organic molecules that are rarely seen elsewhere in the galaxy.

The new sulfur-bearing molecule adds another layer to this chemical richness.

What Makes This Molecule Special

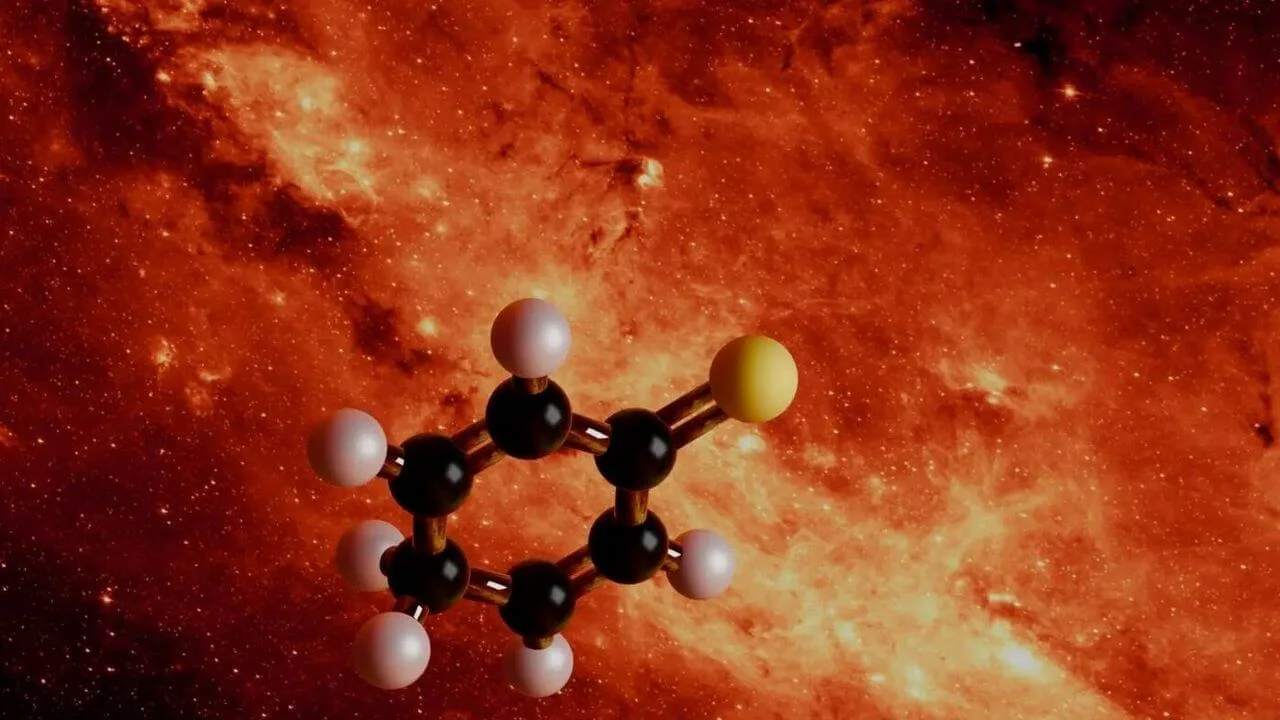

The compound identified by the researchers is called 2,5-cyclohexadien-1-thione. While the name is technical, its structure is easier to understand.

It consists of six carbon atoms arranged in a ring, with a sulfur atom double-bonded to one of the carbons. This ring shape matters. Cyclic molecules are harder to form than straight chains, especially in the cold and sparse environment of space.

Until now, sulfur molecules found in space were mostly small and simple. This newly identified compound is the largest sulfur-containing molecule ever detected in the interstellar medium.

Its size and structure suggest that sulfur chemistry in space can go further than scientists once thought.

The Role of Laboratory Work

The discovery began on Earth, not in space.

Before astronomers can identify a molecule in space, they need to know exactly what signal to look for. Molecules emit and absorb radio waves at very specific frequencies, depending on how their atoms are arranged. These signals act like fingerprints.

In the laboratory, the research team produced the molecule under controlled conditions and measured its rotational spectrum using a high-precision microwave spectrometer. This instrument captures how molecules rotate and emit radiation at radio frequencies.

These measurements created a detailed reference map. Only after this step could astronomers confidently search for the molecule in telescope data.

Without this laboratory groundwork, the molecule would have remained invisible in space.

Finding the Signal in a Crowded Spectrum

The team then examined radio observations of G+0.693–0.027 collected during spectral surveys of the Galactic Center. These surveys record thousands of emission lines from many different molecules, often overlapping and blending together.

Picking out a new molecule from this chemical crowd is not easy.

In this case, the researchers identified multiple emission lines that matched the laboratory fingerprint of 2,5-cyclohexadien-1-thione. The lines appeared at the right frequencies and showed the expected relative strengths.

Seeing several matching lines reduced the chance of coincidence. Together, they provided strong evidence that the molecule was truly present in the cloud.

Why Sulfur Chemistry Matters

Sulfur is not just another element drifting through space. On Earth, it plays a key role in metabolism and cellular structure.

Many scientists are interested in how sulfur-bearing molecules might form before planets exist. If such molecules are already present in interstellar clouds, they could later be incorporated into comets, asteroids, and young planets.

Over time, these materials might deliver complex chemistry to planetary surfaces, including early Earth.

The newly detected molecule is not biological, but it shows that sulfur can be part of relatively complex organic structures in space. This widens the range of chemical building blocks available long before life begins.

A Link to the Early Solar System

Meteorites and comet samples often contain sulfur-rich organic material. Some of these compounds are thought to be older than the planets themselves.

This raises an important question. Did this chemistry form inside the early Solar System, or was it inherited from interstellar space?

The detection of a large sulfur ring molecule in a distant molecular cloud supports the idea that at least some complex sulfur chemistry predates planet formation. These molecules could form in space, stick to dust grains, and later become part of forming planetary systems.

In that sense, the chemistry seen near the Galactic Center may resemble the chemical starting conditions of our own Solar System.

Rethinking the Sulfur Depletion Problem

For decades, astronomers have struggled to account for sulfur in space. If sulfur is present but not detected, it must be hiding somewhere.

One possibility is that sulfur becomes locked into solid dust grains. Another is that it forms molecules that are difficult to detect without precise laboratory data.

This new discovery supports the second idea. It shows that sulfur can be tied up in larger, more complex organic molecules that were simply not being searched for before.

As more laboratory spectra become available, astronomers may begin to recover more of the galaxy’s missing sulfur.

How Might These Molecules Form?

The study does not pin down exactly how the molecule formed, but it offers some hints.

In environments like the Galactic Center, energetic processes such as shocks and cosmic rays can trigger chemical reactions both in the gas and on the surfaces of icy dust grains. These reactions may allow sulfur atoms to attach to carbon rings or help rings form in the first place.

Some molecules may form on dust grains and later be released into the gas when temperatures rise or shocks pass through the cloud.

Understanding these pathways will require further experiments and chemical modeling.

Important Limits to Keep in Mind

The molecule was detected in a very specific and extreme environment. It is not yet clear whether similar sulfur-bearing rings exist in calmer star-forming regions.

Its abundance is also relatively low compared to simpler molecules. While important chemically, it does not by itself solve the sulfur depletion problem.

Still, its detection proves that such chemistry is possible and observable.

That alone is a meaningful step forward.

What This Means for Future Research

The discovery highlights how closely laboratory chemistry and astronomy are linked. Many interstellar molecules likely remain undetected simply because their spectral fingerprints have not yet been measured.

As laboratory techniques improve and telescope surveys expand, scientists expect to identify more complex sulfur compounds in space.

Each new molecule helps refine our understanding of how chemical complexity builds up across the galaxy.

A Small Discovery With Big Implications

This finding does not claim that life began in space. It does something more careful and more solid.

It shows that sulfur, an element essential to biology, can form complex organic structures far from planets and living systems.

Step by step, such discoveries help connect the chemistry of interstellar clouds to the materials that eventually shape planets, and perhaps life itself.

The research was published in Nature Astronomy on January 23, 2026.

This content has been reviewed by subject-matter experts to ensure scientific accuracy. Learn more about us and our editorial process.

Last reviewed on .

Article history

- Latest version

- Peer reviewed by Dr. Arjun Patel, PhD

Reference(s)

- Araki, Mitsunori., et al. “A detection of sulfur-bearing cyclic hydrocarbons in space.” Nature Astronomy, 23 January 2026, doi: 10.1038/s41550-025-02749-7. <https://www.nature.com/articles/s41550-025-02749-7>.

Cite this page:

- Posted by John Williams