The World’s Slowest Science Experiment Has Been Running for Nearly a Century

Since 1927, a strange physics experiment has been quietly running in Australia, showing how a material that looks solid can slowly flow like a liquid, taking years to form a single drop.

In a university building in Australia, there is a glass funnel that seems completely lifeless.

It holds a shiny black substance that looks hard and unmoving. You could easily believe nothing is happening there. Days pass. Months pass. Even years go by, and still it appears frozen.

But this calm is misleading.

Very slowly, almost too slowly for human eyes to notice, the material inside the funnel is moving. After many years of waiting, gravity finally pulls a single drop down. The drop stretches, becomes thinner, and then, suddenly, it falls into a glass container below.

This is the Pitch Drop Experiment, often called the world’s longest-running laboratory experiment. It started in 1927 and, remarkably, it is still going on.

Pitch is a thick, sticky substance made from tar. For a long time, people have used it to seal boats and protect surfaces from water. If you touch pitch, it feels solid. If you hit it hard, it can even crack or break.

So it behaves like a solid. At least at first glance. In reality, pitch is a liquid, but an extremely thick one. Scientists describe this thickness as viscosity. Compared to water, pitch is around 100 billion times more viscous. That means it flows so slowly that the movement is almost invisible.

The idea behind the experiment was simple. If pitch is truly a liquid, then given enough time, it should flow and eventually drip. The difficult part was not setting up the experiment. The difficult part was waiting.

The experiment was started by physicist Thomas Parnell at the University of Queensland. In 1927, Parnell heated pitch until it softened enough to pour. He then filled a glass funnel with the hot material and sealed it. The pitch was left to cool and settle for several years.

In 1930, Parnell cut open the narrow stem of the funnel. From that moment onward, the experiment officially began. Gravity was allowed to do its work.

Then came the long silence. It took eight years for the first drop to finally fall. When it did, it confirmed what Parnell had hoped to show. Pitch does flow. It just does so on a timescale that feels almost unreal.

After the first drop, scientists noticed a pattern. A new drop formed and fell roughly every eight years. That alone makes this experiment unusual. Most scientific experiments produce results quickly. Some take months. A few take years. This one takes decades.

By now, almost 100 years later, only nine drops have fallen in total. The most recent drop fell in 2014. Temperature has played an important role in slowing things down even more. In the 1980s, air conditioning was installed in the building where the experiment is kept. Cooler air made the pitch thicker, which further reduced the speed of the flow.

So the waiting became even longer.

One of the most surprising facts about the Pitch Drop Experiment is that no scientist has ever actually seen a drop fall with their own eyes.

This sounds strange, but there is a reason. A drop forms slowly over many years, but the final moment when it breaks free happens very quickly. Unless someone is watching at exactly the right second, the moment is missed.

Scientists tried to solve this problem by installing cameras and live video feeds. Still, bad luck continued. Power failures, camera issues, and even storms interrupted recordings at the worst possible times. Each time a drop fell, it did so without an audience.

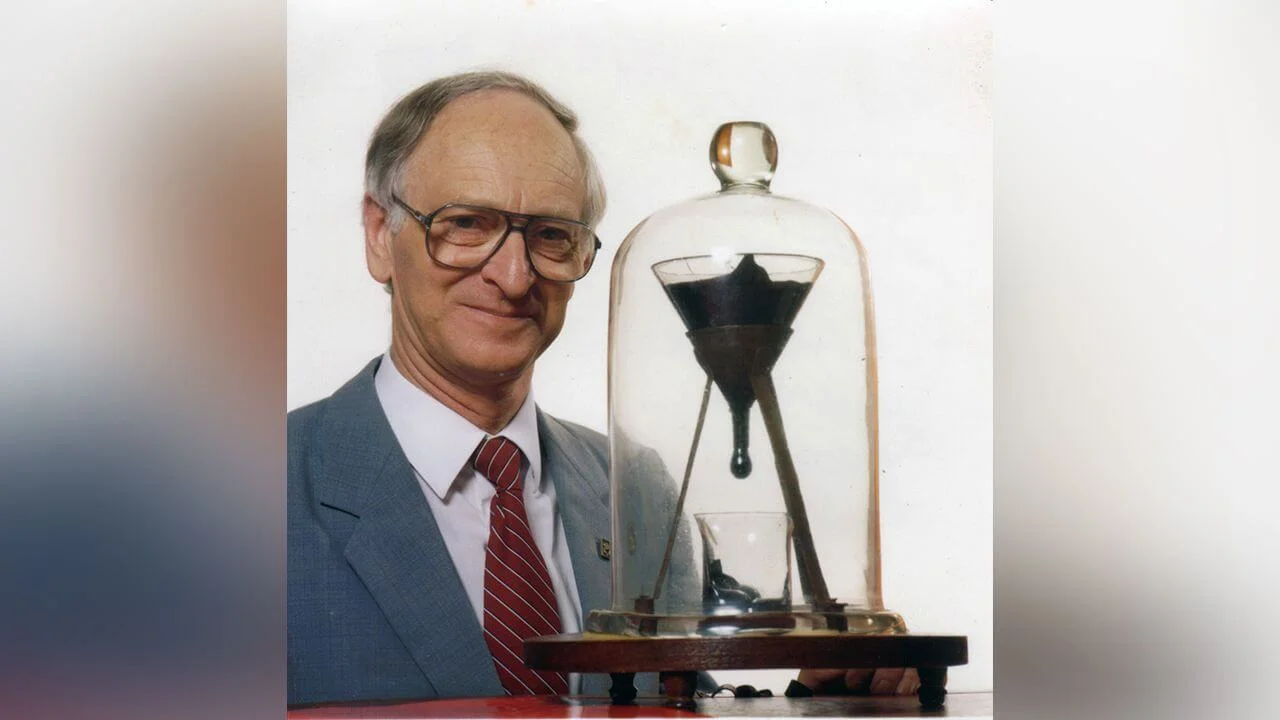

The experiment has lasted longer than the careers and lives of the scientists who cared for it. After Thomas Parnell, the responsibility passed to physicist John Mainstone in 1961. Mainstone became deeply attached to the experiment and looked after it for more than 50 years.

Despite his dedication, he never saw a drop fall either. In one painful moment, a thunderstorm disrupted the live video feed just as a drop fell in 2000.

Mainstone passed away in 2013. Less than a year later, another drop finally fell.

Today, the experiment is watched over by physics professor Andrew White. He is the third custodian in its history and continues the long wait, knowing that the next drop may fall when no one is present.

At first, the Pitch Drop Experiment seems like a curiosity. A slow drip. A long wait. Not much action.

But its message is deeper. It challenges how we define solids and liquids. In daily life, the difference seems clear. Solids keep their shape. Liquids flow. Pitch shows that this distinction depends on time.

Over short periods, pitch behaves like a solid. Over decades, it flows like a liquid. This reminds us that nature does not always fit neatly into human categories.

Very few experiments are designed with the understanding that the original scientist will never see the final result.

The Pitch Drop Experiment was different from the beginning. Parnell knew he was starting something that would continue long after him. The same became true for Mainstone. And it may also be true for the current caretaker.

In a world where results are expected quickly, this experiment feels almost out of place. Yet it quietly shows the value of patience, long-term thinking, and trust in scientific ideas.

The Pitch Drop Experiment is not just about pitch. It is about how slow processes shape the world around us. Many changes in nature happen too slowly for us to notice. Rocks flow. Continents move. Even materials we think are stable are slowly changing.

This experiment makes that idea visible. It turns something abstract into something you can point to and say, “Look, it really is moving.”

Scientists expect another drop to fall sometime in the coming years, but no one can say exactly when. The pitch follows its own schedule.

For now, the funnel hangs quietly. The beaker waits below. And the pitch continues its slow journey downward, reminding us that not all science is fast, and not all discoveries come with excitement and noise.

Some arrive as a single drop, after years of waiting.

This article has been fact checked for accuracy, with information verified against reputable sources. Learn more about us and our editorial process.

Last reviewed on .

Article history

- Latest version

Reference(s)

- Wikipedia. “Pitch drop experiment.” Wikipedia <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pitch_drop_experiment>.

- Guinness World Records. “Longest-running laboratory experiment.” Guinness World Records <https://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/world-records/longest-running-laboratory-experiment>.

- Wikipedia. “Pitch (resin).” Wikipedia <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pitch_(resin)>.

- Stafford, Andrew. “‘It’s literally slower than watching Australia drift north’: the laboratory experiment that will outlive us all.”, 29 April 2022 The Guardian <https://www.theguardian.com/education/2022/apr/30/its-literally-slower-than-watching-australia-drift-north-the-laboratory-experiment-that-will-outlive-us-all>.

Cite this page:

- Posted by John Williams