The Milky Way Galaxy: Scientific Overview of Structure and Evolution

The Milky Way’s story is written in chemical fingerprints and stellar streams, revealing a complex history of ancient mergers and a future trajectory toward a massive collision with Andromeda.

For most of human history, people saw the Milky Way as a pale, cloudy stripe stretched across the night sky. It appeared quietly overhead on clear nights, changing its position with the seasons. There was no idea of galaxies back then. Still, early thinkers paid close attention and tried to explain what they were seeing.

In ancient Greece, philosophers offered different explanations. Aristotle believed the Milky Way was caused by sunlight interacting with gases high in Earth’s atmosphere. Democritus, on the other hand, suggested something far bolder. He proposed that the glow came from a huge number of distant stars packed closely together. At the time, this idea sounded speculative. Today, it sounds surprisingly modern.

Everything changed in the early 1600s when Galileo Galilei pointed his telescope at the Milky Way. What looked smooth to the naked eye suddenly broke apart into countless faint stars. The soft glow was not a mist or vapor at all. It was light from stars too dim and too crowded to be seen individually. This moment marked a turning point. The Milky Way was no longer just a sky feature. It was the first hint of a vast stellar system.

Contributions of Islamic, Asian, and European Astronomers

During the medieval period, Islamic astronomers played a key role in preserving and improving astronomical knowledge. Scholars like Al-Sufi carefully observed the sky and described the Milky Way as a cloudy band made up of innumerable stars. Even without telescopes, their detailed records showed remarkable insight. Their work bridged ancient Greek ideas and later European science.

In East Asia, Chinese astronomers observed the sky continuously for centuries. They called the Milky Way the Silver River and wove it into stories and seasonal traditions. More importantly, they kept careful notes. These records include descriptions of sudden bright stars, now known as novae and supernovae, that appeared within the Milky Way. Today, these historical notes help modern scientists understand past cosmic events.

By the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, European astronomers began to study the Milky Way in a more systematic way. William Herschel attempted one of the first rough maps of its shape by counting stars in different directions. His model had limits because interstellar dust blocked much of the view. Even so, his work pushed astronomy forward. The Milky Way started to be treated as a real structure with form and scale, not just a glowing band in the sky.

Modern Observational Techniques

Optical Astronomy and Star Surveys

Optical astronomy still plays a major role in studying the Milky Way. Powerful ground-based telescopes measure where stars are, how bright they appear, and how their light is spread across different wavelengths. This information tells astronomers about a star’s temperature, chemical makeup, and motion.

Large star surveys have taken this work to another level. Modern projects now map hundreds of millions of stars across wide areas of the sky. With these massive datasets, scientists can trace spiral arms, identify different stellar populations, and piece together how the Milky Way formed over time. It is slow, careful work, but the picture it reveals is far more detailed than anything before.

Infrared and Radio Observations

Much of the Milky Way cannot be seen with visible light alone. Thick clouds of interstellar dust block the view, especially toward the galactic center. Infrared astronomy solves this problem by looking at longer wavelengths that pass through dust more easily. With infrared eyes, astronomers can see hidden stars, active star-forming regions, and the dense central bulge of the galaxy.

Radio astronomy adds yet another layer. Radio telescopes detect cold gas, including neutral hydrogen and molecular clouds. By mapping hydrogen emissions, astronomers measure how fast different parts of the Milky Way rotate. This helps reveal the galaxy’s overall structure and the shape of its spiral arms. Radio observations also track natural masers, which act like precise distance markers scattered across the galaxy.

Space-Based Telescopes and Missions

Observing from space avoids the blurring and absorption caused by Earth’s atmosphere. Space telescopes, working across many wavelengths, have transformed how we see the Milky Way. Ultraviolet and X-ray observatories expose energetic processes, from massive hot stars to the remains of exploded supernovae and matter falling onto compact objects.

Among all these missions, Gaia stands out. It is measuring the positions and motions of more than a billion stars with extraordinary accuracy. The result is a true three-dimensional map of the Milky Way. With it, astronomers can follow stellar orbits, spot streams left behind by ancient mergers, and watch the galaxy evolve in motion, not just in snapshots.

Taken together, these modern tools show the Milky Way as a living system. From our small position inside it, we are slowly learning its shape, its history, and its ongoing story, one observation at a time.

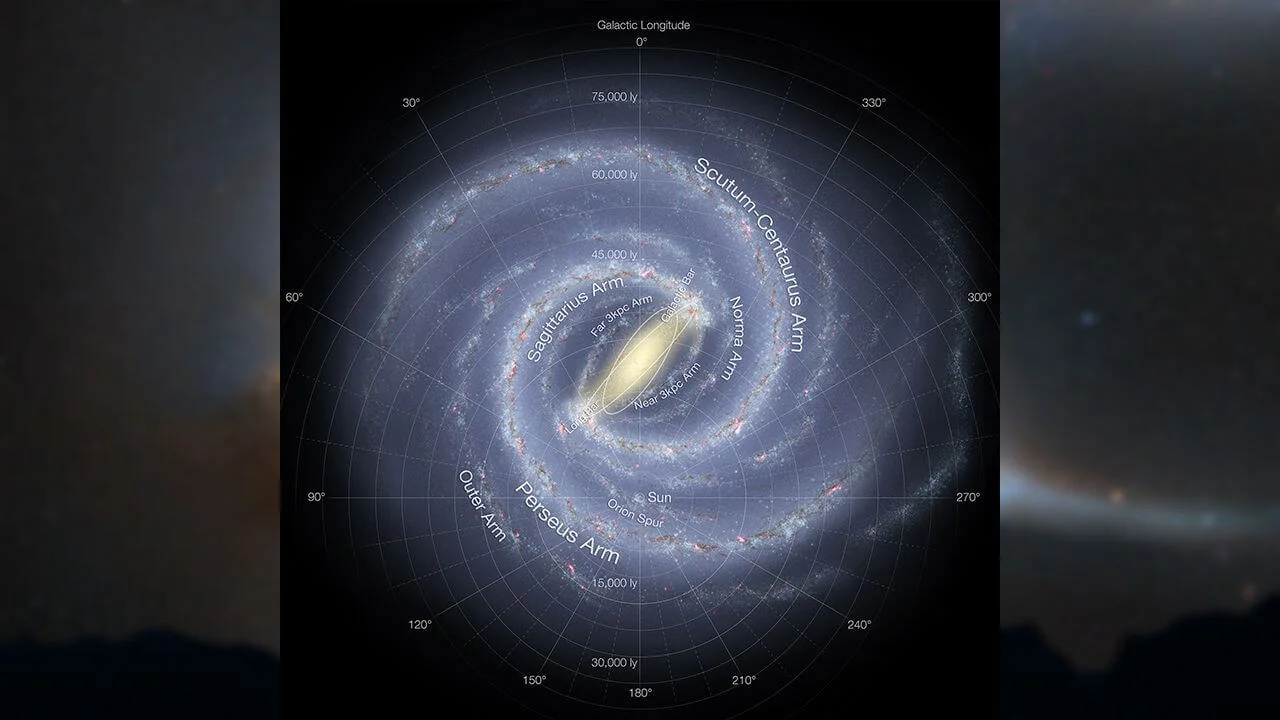

Galactic Classification: Barred Spiral Galaxy Characteristics

The Milky Way is known as a barred spiral galaxy, a label that says a lot in just a few words. Picture a large, flat disk with sweeping spiral arms curling outward, and right at the center, a dense region crossed by a straight, glowing bar of stars. That bar is not just there for looks. It actively shapes how the galaxy behaves.

Astronomers did not spot this bar easily at first. Dust blocks much of the central region when viewed in visible light. Infrared surveys changed that. By looking through the dust, scientists found an elongated group of older stars stretching out from the galactic center. Computer simulations back this up, showing that bars like this often form naturally as spiral galaxies age and their disks become less stable. In many ways, the Milky Way is doing what spiral galaxies tend to do.

Major Structural Components

1. Galactic Disk

The galactic disk is where most of the action happens. It holds the majority of the Milky Way’s stars, along with gas and dust, all rotating together in a broad, thin plane. Compared to its width, the disk is surprisingly thin, almost like a cosmic pancake.

This disk is usually split into two parts. The thin disk contains younger stars that are rich in heavier elements and closely tied to active star formation. The thick disk sits above and below it and is made up of older stars that move more energetically in the vertical direction. Their motions suggest a rougher early history, possibly shaped by ancient collisions or strong internal turbulence.

2. Spiral Arms and Star-Forming Regions

The spiral arms are among the most eye-catching features of the Milky Way, yet they are not fixed structures. Instead, they act like slow-moving traffic jams in the disk. As gas drifts into these denser regions, it gets squeezed, and new stars are born.

That is why spiral arms shine with bright, massive stars and glowing clouds of ionized gas. These stars do not live long, so their presence marks places where star formation is happening right now. Mapping the Milky Way’s spiral arms is tricky because we are stuck inside the disk. Even so, radio observations of gas and careful distance measurements to star-forming regions have helped astronomers sketch out their general layout. The arms keep changing, shaped by rotation and gravity over millions of years.

3. Central Bulge and Galactic Bar

At the very center of the Milky Way sits the galactic bulge, a dense, rounded cluster of stars. Most of these stars are old, which tells scientists that the bulge formed early, when the galaxy itself was still taking shape. Running through this region is the galactic bar, the same structure that defines the Milky Way’s overall classification.

The bar acts like a conveyor belt. It pulls gas inward from the disk toward the center. This flow of material fuels bursts of star formation near the core and affects the environment around the supermassive black hole. At the same time, the bar reshapes stellar orbits across the inner galaxy, tightly linking the fate of the bulge and the disk.

4. Galactic Halo

Beyond the bright disk and central bulge lies the galactic halo, a huge and faint region that stretches far into space. It contains very old stars, some of the oldest known in the Milky Way. Many of them move in long streams, which are the shredded remains of smaller galaxies that were pulled apart and absorbed long ago.

The halo is also where dark matter dominates. This invisible material outweighs normal matter by a wide margin. Even though we cannot see it, the dark matter halo controls the galaxy’s gravity on large scales. It keeps the Milky Way stable and guides the motion of stars and gas everywhere else. Without it, the galaxy as we know it simply would not hold together.

The Galactic Center Environment

Sagittarius A*

Evidence for a Supermassive Black Hole

Deep in the middle of the Milky Way sits Sagittarius A*, a small but powerful radio source located about 26,000 light years away, in the direction of the constellation Sagittarius. It does not shine brightly like the blazing cores of some distant galaxies. In fact, it looks surprisingly quiet. Even so, its gravity tells a very different story.

Careful measurements show that a mass equal to about four million Suns is squeezed into a region smaller than our Solar System. There is no known object, other than a supermassive black hole, that can pack so much mass into such a tiny space. That conclusion did not come quickly. It took patience, precision, and many years of observation.

The strongest proof comes from watching stars near the galactic center move. Astronomers have tracked individual stars for decades as they race around an invisible object. These stars follow neat, closed orbits and reach incredible speeds. Their motion fits the laws of gravity perfectly, allowing scientists to calculate both the mass and the compact size of Sagittarius A*. Every result points to the same answer.

Stellar Orbits and Extreme Gravity

The stars closest to Sagittarius A* live in an extreme environment. Their paths are stretched into long, oval-shaped orbits that carry them from relatively calm regions into zones where gravity becomes overwhelming. As they swing close to the center, their speed jumps to thousands of kilometers per second.

These close passes turn the galactic center into a natural testing ground for Einstein’s theory of general relativity. In recent years, astronomers have detected subtle effects predicted by the theory. Starlight shifts to longer wavelengths due to gravity, and the stars’ orbits slowly rotate over time. Even under these intense conditions, gravity behaves exactly as Einstein said it should.

High-Energy Phenomena

X-Ray and Gamma-Ray Sources

The central few hundred light years of the Milky Way are crowded, messy, and energetic. X-ray and gamma-ray telescopes reveal a busy scene filled with neutron stars, stellar-mass black holes, and the remains of exploded stars. Hot gas, heated to tens of millions of degrees, fills much of the region, glowing brightly at high energies.

Today, Sagittarius A* is relatively calm. Still, there are signs that it was far more active in the past. Nearby molecular clouds glow faintly in X-rays, acting like cosmic mirrors. They appear to be reflecting powerful outbursts that happened long ago, when the black hole briefly flared to life.

Fermi Bubbles

One of the most dramatic discoveries linked to the galactic center is the Fermi Bubbles. These enormous structures rise tens of thousands of light years above and below the plane of the Milky Way. They glow in gamma rays and have sharp, well-defined edges, which makes them hard to ignore.

What caused them is still debated. Some scientists think intense star formation and many supernova explosions near the center pushed energy outward. Others argue that Sagittarius A* itself went through an active phase, blasting material into space. Either way, the message is clear. The heart of the Milky Way can affect the entire galaxy on truly massive scales.

Stellar Populations and Distribution

Stellar Populations I, II, and III

Astronomers group stars in the Milky Way into different populations based on age, chemical makeup, and where they are found. This system helps tell the long story of how the galaxy grew and changed over billions of years.

Population I stars are relatively young and rich in heavy elements. They live mostly in the galactic disk, especially along spiral arms where new stars are still forming. The Sun is one of them, along with many bright, blue stars that light up star-forming regions.

Population II stars are much older and contain far fewer heavy elements. They are common in the galactic halo and central bulge. Their simple chemistry reflects a time when the galaxy was young and had not yet been enriched by many generations of stars.

Population III stars are the first stars ever formed, at least in theory. They were made almost entirely of hydrogen and helium, shortly after the Big Bang. None have been seen directly, but models suggest they existed and lived fast, violent lives. Their explosions likely created the first heavy elements in the universe.

Age and Metallicity Differences

In the Milky Way, age and metal content are closely connected. Older stars tend to be metal poor because they formed before earlier stars had time to enrich the surrounding gas. By studying the elements in a star’s atmosphere, astronomers can estimate when and where it was born.

Large surveys now map these chemical patterns across the galaxy. The inner regions are generally richer in metals, while the outer disk and halo contain stars with lower metal content. These gradients preserve a record of star formation, gas flows, and ancient mergers that shaped the Milky Way.

Star Clusters

Open Clusters in the Disk

Open clusters are loose families of stars that formed together from the same cloud of gas. They usually contain dozens to thousands of stars and are found almost entirely in the galactic disk. Most are young, ranging from a few million to a few billion years old.

Because the stars in an open cluster share the same age and composition, these clusters are perfect testing grounds for studying how stars evolve. Over time, however, gravity and passing clouds slowly pull them apart, spreading their stars into the wider disk.

Globular Clusters in the Halo

Globular clusters are very different. They are dense, tightly bound spheres containing hundreds of thousands of stars. These clusters orbit the Milky Way in the halo or pass through the bulge, and many are more than 10 billion years old.

Their stars are metal poor, showing they formed early, when the universe was still chemically simple. Some globular clusters even show signs of multiple generations of stars, hinting at a more complex history than once believed. Taken together, these ancient clusters act like fossils, preserving a record of the Milky Way’s earliest days.

Interstellar Medium of the Milky Way

The space between stars in the Milky Way may look empty at first glance, but it is anything but. This vast space is filled with gas, dust, magnetic fields, and fast-moving particles called cosmic rays. Together, these ingredients are known as the interstellar medium. It is both a beginning and an ending point. New stars are born from it, and old stars return material back into it when they die.

In this way, the interstellar medium connects one generation of stars to the next. It quietly controls how the galaxy grows, changes, and keeps renewing itself over time.

Gas Components

1. Molecular Clouds

Molecular clouds are the coldest and densest parts of the interstellar medium. They are made mostly of molecular hydrogen, a gas that is hard to see directly. Instead, astronomers track these clouds using carbon monoxide, which shines clearly at radio wavelengths. Some of these clouds stretch across tens or even hundreds of light years and hold enough material to form thousands of stars.

Inside a molecular cloud, several forces are at work. Gravity pulls inward, while pressure, turbulence, and magnetic fields push back. When gravity finally wins, parts of the cloud begin to collapse. That slow collapse marks the first step toward star formation. Because of this, molecular clouds map out where future stars will appear in the galactic disk.

2. Atomic and Ionized Gas

Beyond the dense molecular regions, much of the interstellar medium exists as atomic hydrogen. This gas is thinner and more spread out, filling large areas of the Milky Way’s disk and even extending into the halo. Its signature 21-centimeter radio signal has been one of the most important tools for mapping the galaxy and measuring how it rotates.

There is also ionized gas, which represents a hotter and more energetic state. This gas is commonly found near massive stars that pour out intense ultraviolet radiation. That radiation strips electrons from nearby atoms. On larger scales, ionized gas spreads through the galaxy, kept energized by starlight, supernova shocks, and cosmic rays moving through space.

Cosmic Dust

Role in Star Formation

Cosmic dust makes up only a small fraction of the interstellar medium, but its impact is huge. These tiny grains provide surfaces where molecules can form, including molecular hydrogen, which is essential for star formation. Dust also helps gas clouds cool by releasing energy in the infrared. Cooler gas collapses more easily under gravity.

By shaping the temperature and chemistry of star-forming regions, dust quietly controls how fast and how efficiently stars form. Without it, the Milky Way would look very different, and star birth would be far less effective.

Light Absorption and Reddening

Dust does more than help form stars. It also affects how we see the galaxy. Dust grains absorb and scatter starlight, especially blue light, making distant stars appear dimmer and redder. This effect is known as interstellar reddening. Astronomers must correct for it to accurately measure distances, brightness, and true colors of stars.

At the same time, dust re-radiates the absorbed energy as infrared light. Because of this, the Milky Way shines strongly in infrared wavelengths. Infrared observations reveal hidden regions that visible light cannot reach, offering a clearer and more complete view of the galaxy’s inner workings.

Star Formation Across the Galaxy

Star formation in the Milky Way does not happen everywhere. It is concentrated in special environments where gas becomes dense and cool enough for gravity to take control. These regions are closely linked to the structure of the galactic disk and the winding spiral arms.

Giant Molecular Clouds

Giant molecular clouds are the main birthplaces of stars. They are massive, cold structures dominated by molecular hydrogen and traced using radio emissions from carbon monoxide and other molecules. Some of these clouds contain millions of times the mass of the Sun and span dozens of light years.

Inside them, turbulence creates a tangled network of filaments and dense knots. Gravity works best in the densest spots, where collapse begins. Interestingly, only a small fraction of a cloud’s total mass turns into stars. The rest is eventually pushed back into the interstellar medium, ready to be recycled.

Stellar Nurseries and H II Regions

As dense regions collapse, protostars form and slowly heat their surroundings. When massive young stars finally ignite nuclear fusion, their strong ultraviolet light ionizes nearby hydrogen gas. This creates H II regions, which glow brightly and stand out in both optical and radio images.

These glowing regions often trace spiral arms and highlight where star formation is happening right now. Within them, clusters of stars are common. Stars usually form in groups, not alone, and a wide range of stellar sizes can emerge from the same cloud.

Feedback From Massive Stars

Stellar Winds

Massive stars do not stay quiet during their short lives. They release powerful stellar winds that blast outward at high speeds, pumping energy into the surrounding gas. These winds can hollow out cavities in molecular clouds and pile up gas along the edges.

Sometimes, this compression sparks new rounds of star formation. Other times, it tears the cloud apart and stops further collapse. In this way, stellar winds both encourage and limit star birth, keeping the process in balance.

Supernova Explosions

The most dramatic feedback comes at the end of a massive star’s life. When such a star explodes as a supernova, it releases an enormous amount of energy in a single event. Shock waves race through the interstellar medium, heating gas and scattering heavy elements created inside the star.

These explosions reshape the galactic disk over time. The enriched material mixes with surrounding gas, providing the building blocks for future stars and planets. Through this cycle, the Milky Way continues to evolve, driven by the constant exchange of matter between stars and the space around them.

Galactic Dynamics and Rotation

The Milky Way is not sitting still. It is a vast, rotating system, and that motion carries important clues about what the galaxy is made of, including things we cannot see. By tracking how stars and gas move through space, astronomers can work out the galaxy’s mass, its structure, and whether it can remain stable over billions of years.

Galactic Rotation Curve

The galactic rotation curve shows how fast stars and gas orbit the center of the Milky Way at different distances. If most of the galaxy’s mass were packed into its bright central regions, the story would be simple. Objects farther out would move more slowly, just like planets do as you move away from the Sun.

That is not what astronomers observe. Beyond the inner parts of the galaxy, stars and gas keep circling the center at nearly the same speed, even far from most of the visible matter. This flat rotation curve was a surprise and remains one of the strongest pieces of evidence that something unseen is shaping the galaxy.

Evidence for Dark Matter

The fact that outer stars move so fast means there must be extra mass providing additional gravity. This unseen mass is known as dark matter, and it appears to form a large halo surrounding the Milky Way. Without it, stars at the edge of the galaxy would simply drift away.

Observations of neutral hydrogen gas played a key role here. This gas extends well beyond the visible disk and follows the same flat rotation pattern. Similar behavior is seen in other spiral galaxies too, showing that dark matter is not unique to the Milky Way. It seems to be a basic feature of galaxies across the universe.

Orbital Motion of Stars

Stars in the Milky Way follow many different paths. Their orbits depend on where they are and when they formed. Most disk stars travel on nearly circular paths within the galactic plane. Halo stars, in contrast, move along stretched and tilted orbits that take them far above and below the disk.

High-precision measurements have revealed groups of stars moving together in long streams. These are the remains of smaller galaxies that were pulled apart and absorbed by the Milky Way long ago. Their motions preserve a kind of memory, allowing astronomers to reconstruct parts of the galaxy’s growth history.

Differential Rotation of the Disk

The Milky Way also shows differential rotation. This means that different parts of the disk rotate at different speeds. The inner regions complete an orbit around the galactic center faster than the outer ones. Over time, this difference stretches material across the disk.

This process helps shape spiral arms and influences where stars can form. It also slowly mixes stellar populations, spreading stars that were born together across wide areas. To understand today’s motions, astronomers must take this constant shearing and mixing into account.

Dark Matter in the Milky Way

Dark matter makes up most of the Milky Way’s mass. It does not give off light or interact with it in any direct way, yet its gravitational pull is impossible to miss. From the bright inner disk to the faint outer halo, dark matter controls how stars and gas move.

Observational Evidence

Rotation Curves

The rotation curve remains the clearest sign of dark matter. Stars and gas far from the center orbit just as fast as those much closer in. Visible matter alone cannot produce this effect.

If the galaxy contained only stars, gas, and dust, orbital speeds would drop with distance. Instead, the flat curve points to a huge amount of unseen mass spread far beyond the luminous disk.

Gravitational Effects on Satellites

More evidence comes from objects orbiting the Milky Way. Satellite galaxies and globular clusters move as if they are bound by a strong gravitational field. The visible mass of the Milky Way is not enough to explain their speeds.

Stellar streams provide another clue. These long trails of stars form when smaller galaxies are torn apart by tidal forces. Their shapes and paths trace the underlying gravitational landscape, offering a detailed look at how dark matter is arranged in the halo.

Dark Matter Halo Models

To make sense of all this, astronomers model the Milky Way as sitting inside a massive dark matter halo. This halo is roughly spherical and extends far beyond the galaxy’s visible edge, wrapping around the disk, bulge, and stellar halo.

Different models describe how the density of dark matter changes from the center outward. Some suggest a sharp increase toward the core, while others favor a flatter inner region. By comparing these models with real data, scientists hope to narrow down the true nature of dark matter.

Even after decades of research, no one knows exactly what dark matter is. Still, its influence is undeniable. Without it, the Milky Way could not look or behave the way it does, making dark matter one of the central mysteries in modern astronomy and cosmology.

Chemical Evolution of the Galaxy

The Milky Way did not always look the way it does today, at least not chemically. In the early universe, the galaxy was made almost entirely of hydrogen and helium. Over billions of years, that simple mix slowly changed. New elements were created, scattered, and recycled again and again. This long process is known as the chemical evolution of the galaxy.

Nucleosynthesis in Stars

Stars are the main factories that produce chemical elements heavier than hydrogen and helium. Deep inside their cores, nuclear fusion turns lighter elements into heavier ones. This process releases energy, which is why stars shine for such long periods of time.

Smaller and medium-sized stars create elements like carbon and nitrogen during their lifetimes. As these stars age, they lose material through gentle stellar winds, returning newly made elements back into space. Massive stars go even further. They build elements all the way up to iron in their cores. When they finally explode as supernovae, they create and spread even heavier elements in a violent burst, enriching the surrounding interstellar medium.

Metal Enrichment Over Time

Every new generation of stars forms from gas that has already been processed by earlier stars. Because of this, the overall metal content of the Milky Way has steadily increased. This pattern is easy to see when comparing very old stars in the halo, which are metal poor, with younger stars in the disk that contain far more heavy elements.

This enrichment is not evenly spread across the galaxy. The inner regions of the Milky Way are generally richer in metals than the outer disk. That difference reflects how star formation and gas inflow varied from place to place. Over time, stars migrate and mix, blurring these chemical boundaries and spreading elements across large distances.

Tracing Galactic History Through Elemental Abundances

The mix of elements inside a star acts like a chemical fingerprint. By measuring how much of each element a star contains, astronomers can learn what kinds of supernovae enriched the gas it formed from and how quickly that enrichment happened.

Today, large surveys measure the chemical makeup of millions of stars. These detailed records allow scientists to identify stars that were born together, even if they are now scattered across the galaxy. This approach, known as galactic archaeology, turns chemical evolution into a powerful tool for rebuilding the Milky Way’s past and understanding how it grew.

Satellite Galaxies and Stellar Streams

The Milky Way is not alone in space. It is surrounded by smaller companion galaxies and long streams of stars that tell a story of interaction, growth, and gradual change. Together, these structures provide clear evidence that our galaxy has grown by absorbing smaller systems over billions of years.

Dwarf Galaxies of the Milky Way

Dozens of dwarf galaxies orbit the Milky Way. Some are bright and easy to spot, while others are extremely faint and dominated by dark matter. These small galaxies are chemically simple and contain very old stars, making them ideal places to study early star formation on small scales.

Many dwarf galaxies show complex histories. Some formed most of their stars early in the universe, while others kept forming stars until fairly recently. As they orbit the Milky Way, tidal forces slowly pull them apart, stripping away stars and gas and reshaping them over time.

Large and Small Magellanic Clouds

The largest and most famous companions of the Milky Way are the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds. They are irregular dwarf galaxies rich in gas and active star formation, and they can be seen with the naked eye from the Southern Hemisphere.

The Large Magellanic Cloud contains the Tarantula Nebula, one of the most intense star-forming regions nearby. The two Clouds are linked by a bridge of gas and stars, and together they trail a long stream of hydrogen called the Magellanic Stream. This structure shows that the Clouds are interacting with each other and with the Milky Way’s halo.

Tidal Streams

As dwarf galaxies and globular clusters orbit the Milky Way, gravity stretches them out. Stars are slowly pulled away and spread along their paths, forming long tidal streams that curve across the sky. Some of these streams remain visible for billions of years.

These streams act like fossils from the past. By studying their positions, motions, and chemical signatures, astronomers can retrace the paths of their original systems and map the Milky Way’s gravitational structure.

Remnants of Past Mergers

Some of the most striking streams come from galaxies that are still being torn apart today. The Sagittarius stream, for example, originates from the Sagittarius dwarf galaxy, which is currently breaking up. Its stars now wrap around the Milky Way in long, looping arcs.

Other streams are much older. They are the remains of mergers that happened early in the Milky Way’s history. Their stars often have unusual chemical patterns, showing they formed outside the Milky Way before being absorbed. Together, these remnants reveal a clear picture. The Milky Way grew step by step, through repeated mergers, just as modern models of galaxy formation predict.

The Milky Way in a Cosmological Context

The Milky Way is just one galaxy in a vast and tangled cosmic web. It doesn’t exist in isolation. Gravity links it to its neighbors, and its history is tied up with theirs. To understand our galaxy fully, we have to look both nearby and far, comparing it with other galaxies and exploring its place in the universe.

Membership in the Local Group

Our galaxy belongs to the Local Group, a collection of over 50 galaxies dominated by the Milky Way and the Andromeda Galaxy. This group stretches across roughly 10 million light-years. Smaller galaxies, including dozens of dwarf satellites, orbit these two giants, and their motions are shaped by gravity.

These interactions leave visible marks: stellar streams, tidal tails, and distorted dwarf galaxies all tell stories of past encounters. By studying them, astronomers can see firsthand how galaxies grow, merge, and change over time.

Comparison With Other Spiral Galaxies

The Milky Way is a barred spiral galaxy, a type seen commonly throughout the nearby universe. Its winding spiral arms, central bulge, and flat disk look similar to galaxies like M81 and M83.

By comparing star formation rates, chemical makeup, and dark matter content, astronomers can place the Milky Way on a spectrum of spiral galaxy types. This helps us understand which features are typical for spiral galaxies and which make our galaxy unique.

Future Evolution

Interaction and Merger With Andromeda

In a few billion years, the Milky Way will collide with the Andromeda Galaxy. Estimates put this event at around 4 to 5 billion years from now. Gravity will draw the two giants together, initiating a complex dance that will reshape both systems dramatically.

Simulations suggest that most stars will pass by each other without direct collisions, but gas and dust will crash together, triggering bursts of star formation. Over time, the merger will likely produce a single massive elliptical galaxy, sometimes nicknamed “Milkomeda.” This predicted event shows that galaxies are far from static—they evolve, collide, and transform over cosmic time.

The Sun’s Position in the Milky Way

Our Sun lives in a relatively calm corner of the galaxy. It sits in one of the spiral arms, moving along with a population of nearby stars. Its position and motion play a big role in shaping the environment of the Solar System and maintaining long-term planetary stability.

Location in the Orion Arm

The Sun resides in the Orion Arm, a smaller spiral segment between the larger Perseus and Sagittarius arms. This region is moderately dense, filled with young and old stars, clouds of gas, and active star-forming regions. It is far less crowded than the central bulge but more populated than the distant halo.

At about 26,000 light-years from the galactic center, the Sun travels at roughly 220 kilometers per second. It takes around 225 to 250 million years to complete one full orbit—a period sometimes called a “galactic year.”

Galactic Environment of the Solar System

The Sun’s orbit keeps it close to the mid-plane of the galactic disk. This stable path avoids the dense bulge at the center and the chaotic halo, reducing exposure to dangerous events like nearby supernovae that could disrupt planetary orbits or strip away atmospheres.

Implications for Planetary Stability

Living in a relatively calm part of the Milky Way has allowed the Solar System to remain stable over billions of years. This stability is crucial for processes like the emergence of life on Earth. At the same time, being in a moderately dense environment ensures access to raw materials—gas and dust from nearby star-forming regions—that continue to support planet formation.

Ongoing and Future Research

The Milky Way is still a dynamic puzzle for astronomers. New surveys and space missions are constantly revealing more about its structure, stellar populations, and dark matter content. Technology now allows scientists to map the galaxy in incredible detail, from large-scale features down to subtle substructures.

Major Sky Surveys

Large-scale surveys have transformed galactic astronomy. By tracking positions, motions, and chemical compositions of millions of stars, these surveys allow astronomers to reconstruct the Milky Way’s history with unprecedented clarity.

Gaia Mission

The European Space Agency’s Gaia mission has been revolutionary. It measures precise positions, distances, and motions for over a billion stars. Gaia has mapped streams from disrupted satellite galaxies, traced spiral structures, and improved models of the galaxy’s mass, including its dark matter halo.

Sloan Digital Sky Survey

The Sloan Digital Sky Survey, or SDSS, provides high-quality spectroscopy and imaging for millions of stars and galaxies. It has discovered faint satellite galaxies, characterized stellar populations, and traced chemical abundance patterns that reveal past merger events.

Upcoming Space Missions and Observatories

The next generation of observatories promises even more discoveries. High-resolution surveys in infrared, radio, and other wavelengths will explore dusty regions and reveal the dynamics of stars and gas near the galactic center.

Next-Generation Infrared and Radio Telescopes

Instruments like the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), the Square Kilometre Array (SKA), and future infrared missions will probe deep into the Milky Way’s dusty regions. They will resolve star-forming clouds, detect faint stellar populations, and map tidal streams. These observations will let astronomers test models of galactic evolution with a level of precision that was unimaginable just a few decades ago.

The Milky Way is alive in motion and history, and with every new observation, we see more of its story unfold.

This content has been reviewed by subject-matter experts to ensure scientific accuracy. Learn more about us and our editorial process.

Last reviewed on .

Article history

- Latest version

Reference(s)

- Galilei, Galileo. “Sidereus Nuncius (The Starry Messenger).”, University of Chicago Press, 1989, isbn: 9780226279039. <ttps://books.google.com.pk/books?id=T35ui1e6LIwC>.

- European Space Agency. “Gaia Data Release 3 (DR3).”, 2023 European Space Agency <https://www.cosmos.esa.int/web/gaia/dr3>.

- Genzel, Reinhard., et al. “The Galactic Center massive black hole and nuclear star cluster.” Reviews of Modern Physics, vol. 82, no. 4, 2010 American Physical Society, doi: 10.1103/RevModPhys.82.3121. <https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/RevModPhys.82.3121>.

- Abazajian, Kevork N.., et al. “The Seventh Data Release of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey.” The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, vol. 182, no. 2, 18 May 2009, doi: 10.1088/0067-0049/182/2/543. <https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/0067-0049/182/2/543>.

- NASA. “Milky Way Anatomy: Scientific Visualization Studio.”, 18 December 2025 National Aeronautics and Space Administration <https://svs.gsfc.nasa.gov/14935/>.

Cite this page:

- Posted by Arjun Patel