Tests for Detection of Glucose in Urine

A urine glucose test checks how much sugar is in your urine. If there's too much, it could mean a health issue. If not treated, high glucose levels could indicate a serious condition like type 1 or type 2 diabetes. Find out more about the test.

Glucose, a primary source of energy for the body, is meticulously regulated to maintain optimal physiological functioning. However, when the delicate balance is disrupted, as seen in diabetes, glucose levels in the blood can spill into the urine, signaling an underlying issue. The tests designed for the detection of glucose in urine play a pivotal role in diagnosing and managing diabetes and other metabolic disorders.

1. Copper Reduction Methods

A. Benedict’s qualitative test

When we boil urine in Benedict's solution, a blue copper sulfate turns into a red-brown cuprous oxide, indicating the presence of a reducing agent (see Figure 1). The intensity of this color change relates to how much of the reducing substance is present. It's important to note that while this test provides valuable information, it isn't exclusive to glucose—it can detect various reducing agents in urine.

Some sugars (such as lactose, fructose, galactose, and pentoses), specific body substances (like glucuronic acid, homogentisic acid, uric acid, and creatinine), and various medications (including ascorbic acid, salicylates, cephalosporins, penicillins, streptomycin, isoniazid, para-aminosalicylic acid, nalidixic acid, etc.) also cause a reduction in alkaline copper sulfate solution.

Method

- Get a test tube and put 5 ml of Benedict's qualitative reagent in it. (Benedict's reagent is made up of copper sulfate, sodium carbonate, sodium citrate, and distilled water.)

- Add 0.5 ml (or 8 drops) of urine to the test tube and mix it well.

- Boil the mixture over a flame for 2 minutes.

- Let it cool to room temperature.

- Observe any color change.

The test is sensitive to about 200 mg of reducing substance per dl of urine. While Benedict's test reacts positively with carbohydrates other than glucose, it's also used to screen for inborn errors of carbohydrate metabolism in infants and children, detecting galactose, lactose, fructose, maltose, and pentoses in urine.

If you're only checking for glucose in urine, it's preferable to use reagent strips.

Results are reported in grades as follows:

- Nil: No change from blue color.

- Trace: Green without precipitate.

- 1+ (approx. 0.5 grams/dl): Green with precipitate.

- 2+ (approx. 1.0 grams/dl): Brown precipitate.

- 3+ (approx. 1.5 grams/dl): Yellow-orange precipitate.

- 4+ (> 2.0 grams/dl): Brick-red precipitate.

B. Clinitest tablet method (Copper reduction tablet test):

This test is like the Benedict’s test, but the chemicals are in tablet form (copper sulfate, citric acid, sodium carbonate, and anhydrous sodium hydroxide). It can detect glucose at a sensitivity of 200 mg/dl.

2. Reagent Strip Method

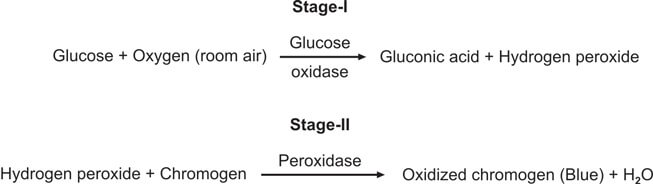

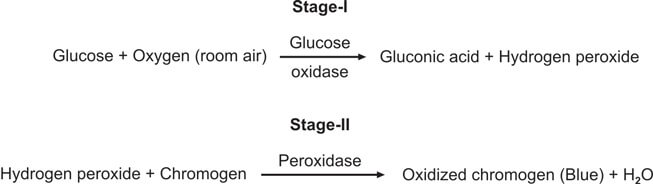

This test is special for checking glucose and is better than Benedict’s and Clinitest methods. It works by using the glucose oxidase-peroxidase reaction. The strip has two enzymes (glucose oxidase and peroxidase) and a color-changing substance. When glucose is present, it reacts with glucose oxidase to make hydrogen peroxide and gluconic acid. The color-changing substance reacts with the hydrogen peroxide, causing a color change (see Figure 3). Different strips have different color substances and buffers.

You dip the strip in the urine, wait for a bit, and then compare the color to a chart (see Figure 2).

This test is better than Benedict’s for finding glucose, and it only reacts to glucose, not other substances.

It can detect about 100 mg of glucose in a deciliter of urine.

However, be aware that the test might show a false positive if there's bleach or hypochlorite (used for cleaning urine containers) around, as they can directly affect the color change.

On the flip side, a false negative might happen if there are lots of ketones, salicylates, ascorbic acid, or a strong Escherichia coli infection. The catalase produced by the bacteria can deactivate the hydrogen peroxide used in the test.

The information on this page is peer reviewed by a qualified editorial review board member. Learn more about us and our editorial process.

Last reviewed on .

Article history

- Latest version

Cite this page:

- Comment

- Posted by Dayyal Dungrela