Sun Simiao’s Ten Commandments for Physicians

Discover how Sun Simiao’s Ten Commandments shaped ancient Chinese medical ethics, uniting compassion, wisdom, and moral duty in healing.

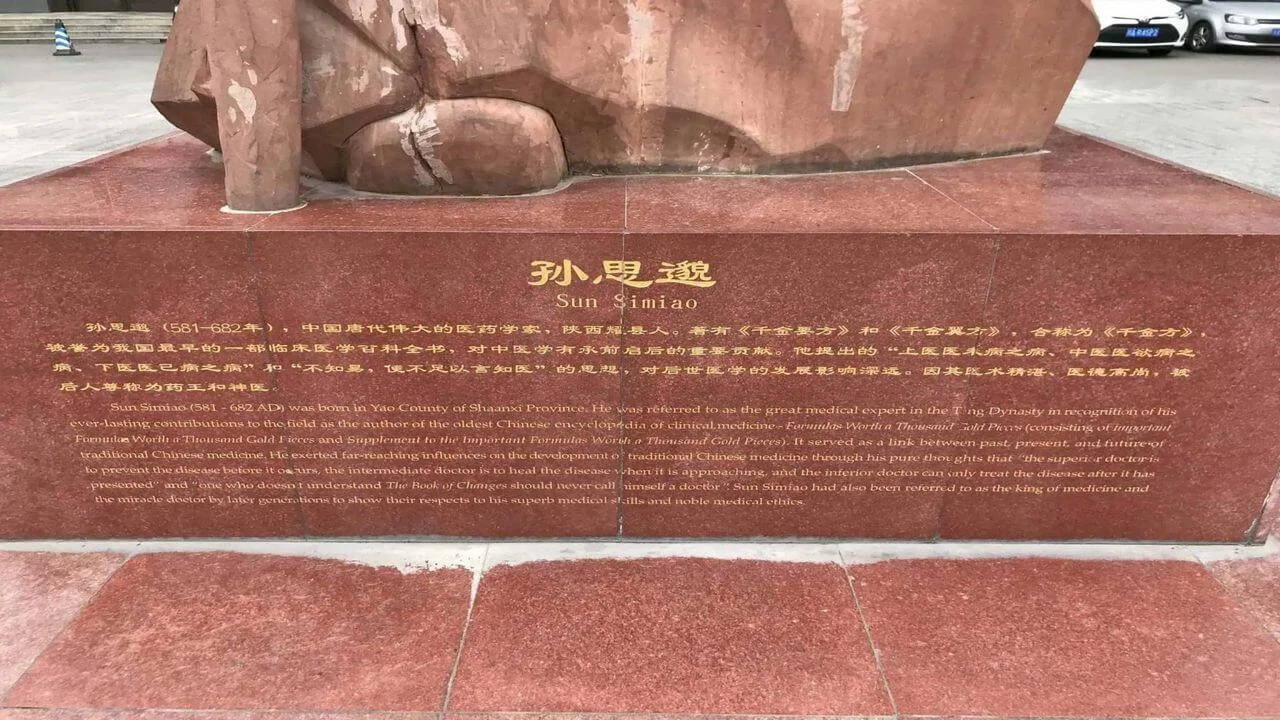

Throughout history, medicine has been seen as both a science and a moral duty. Just as the Hippocratic Oath and the Charaka Shapath served as ethical guides for physicians in Greece and India, the Chinese medical tradition developed its own profound moral philosophy under the guidance of Sun Simiao (581–682 CE). He was not only a physician but also a scholar, philosopher, and alchemist whose contributions extended beyond clinical medicine to the realm of ethics and humanism.

Sun Simiao’s ethical reflections appear in the preface of his classic medical compendium Qianjin Yaofang (Essential Prescriptions Worth a Thousand Gold Pieces), where he presents his Ten Commandments for Physicians. These commandments stress that the physician’s moral virtue is as important as technical expertise, asserting that without compassion and integrity, medicine loses its soul.

Historical Context

The Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE) was one of the most intellectually vibrant periods in Chinese history. It was an era of openness, innovation, and cultural synthesis. Scholars during this time were deeply influenced by the three major philosophical systems of China: Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism.

Sun Simiao, born in what is now Shaanxi Province, was a prodigy known for his vast learning and moral character. By his thirties, he had already mastered classical literature, philosophy, and medicine. Despite his fame, he declined invitations from emperors to serve at the royal court, preferring to live a life of simplicity and service to the common people. His writings demonstrate a deep concern for humanity, particularly the poor and marginalized who often lacked access to medical care.

His two monumental works, Beiji Qianjin Yaofang (Essential Prescriptions Worth a Thousand Gold Pieces for Emergencies) and Qianjin Yifang (Supplement to the Essential Prescriptions Worth a Thousand Gold Pieces), remain key texts in the study of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). However, beyond their pharmacological and clinical knowledge, these works also reflect an ethical vision that defines the ideal physician as a moral, disciplined, and compassionate individual.

The Ten Commandments for Physicians

Sun Simiao’s Ten Commandments form a timeless ethical guide for medical practitioners. While the precise translation may differ, the core principles are consistent across versions. These commandments can be summarized as follows:

- Value all human life equally: A physician must treat every patient with equal care, regardless of wealth, status, age, or background. Human life should be considered sacred and invaluable.

- Treat medicine as a noble duty, not a business: The primary aim of medicine is to alleviate suffering, not to pursue wealth or fame. Physicians must never allow greed or ambition to influence their judgment.

- Show utmost compassion and empathy: A doctor should be moved by a patient’s pain and motivated by genuine concern. Compassion is seen as the heart of healing.

- Maintain patient confidentiality: The physician must protect the privacy and dignity of patients, never disclosing their conditions or using information for personal benefit.

- Remain humble and committed to learning: Medicine is a lifelong pursuit. Arrogance and complacency are signs of moral failure. Continuous study and humility are essential for growth.

- Avoid discrimination of any kind: Treatment should be offered to all, without bias toward gender, ethnicity, religion, or social class. Compassion knows no boundaries.

- Keep one’s intentions pure: Physicians must purify their hearts and minds, avoiding selfish motives, lust, corruption, or pride in their work.

- Respect teachers and medical traditions: Reverence for mentors and respect for classical teachings maintain the integrity and continuity of medicine as a moral profession.

- Exercise caution and wisdom in practice: Accurate diagnosis and careful treatment are moral duties. Recklessness or overconfidence in treatment is considered a form of harm.

- Cultivate moral character and virtue: Healing requires inner balance. A good physician must cultivate patience, kindness, and sincerity, reflecting harmony between moral virtue and medical skill.

These ten principles represent not only professional conduct but also moral cultivation and self-discipline. They emphasize that a physician’s mind and heart must remain pure to truly heal others.

Philosophical Foundations of Sun Simiao’s Ethics

Sun Simiao’s ethical philosophy draws upon the harmonious integration of China’s three major traditions:

- Confucianism emphasizes righteousness, benevolence, and duty. It defines the physician as a moral exemplar responsible for upholding social harmony and ethical conduct.

- Buddhism contributes the concept of compassion and the ideal of relieving all sentient beings from suffering. The physician’s service is seen as a form of spiritual merit.

- Daoism focuses on balance and alignment with nature. Health represents harmony within the human body and between the individual and the cosmos.

By merging these philosophies, Sun Simiao transformed medicine into a path of ethical self-cultivation and spiritual enlightenment. The act of healing became not just a professional task but an expression of moral virtue and inner harmony.

Sun Simiao’s View on the Physician’s Responsibility

Sun Simiao repeatedly emphasized that the physician’s responsibility extends beyond the treatment of disease. The physician must embody benevolence, humility, and compassion. He wrote that “one who practices medicine must develop a heart of great compassion and vow to save all living beings from suffering.”

He urged doctors to visit patients even in difficult conditions and to offer care to those who could not afford it. He also cautioned against exploiting patients, saying that the healer’s motivation should always arise from empathy, not profit.

In Sun Simiao’s view, the physician was a moral agent entrusted with human life, and therefore had a sacred obligation to maintain moral purity and inner peace.

Comparison with Other Ethical Traditions

Sun Simiao’s commandments can be compared to other ancient medical oaths such as the Hippocratic Oath of Greece and the Charaka Shapath of India.

- Like the Hippocratic Oath, his commandments emphasize non-maleficence, confidentiality, and the duty to serve.

- Similar to the Charaka Shapath, they promote self-control, humility, and devotion to the art of healing.

However, Sun Simiao’s ethical vision is unique in its integration of spiritual philosophy, focusing on the physician’s inner cultivation and moral transformation. He viewed healing as an extension of compassion and virtue, rather than merely a professional obligation.

Influence on Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM)

The ethical ideals of Sun Simiao continue to shape the teaching and practice of traditional Chinese medicine. His writings are included in classical medical curricula and are often cited in discussions of modern medical ethics in China.

Contemporary practitioners recognize his Ten Commandments as the foundation of professional conduct in TCM. They serve as a reminder that healing requires more than technical knowledge—it requires a moral consciousness aligned with empathy and integrity.

Relevance to Modern Medicine

In modern times, medicine faces challenges of commercialization, technological dependence, and ethical dilemmas in patient care. Sun Simiao’s teachings remain remarkably relevant. His insistence that a physician must treat patients as equals, prioritize compassion, and uphold integrity resonates deeply with current global medical ethics.

His ideas mirror contemporary values such as:

- Patient-centered care

- Medical professionalism

- Equitable access to healthcare

- Non-discrimination

- Confidentiality and privacy

Modern bioethics frameworks, including the Declaration of Geneva and the World Medical Association’s Code of Ethics, reflect many of the moral principles first articulated by Sun Simiao more than 1,300 years ago.

Legacy and Recognition

Sun Simiao’s legacy endures not only in China but throughout the world. He is honored in temples, medical universities, and scholarly works as the “King of Medicine.” His belief that moral virtue is the root of healing has influenced generations of practitioners.

His philosophy represents the perfect synthesis of science and spirituality, intellect and compassion. By uniting knowledge with morality, he established a timeless model for the physician as a healer of both body and soul.

Conclusion

Sun Simiao’s Ten Commandments for Physicians are far more than ancient guidelines; they are a complete ethical philosophy of medicine. His teachings remind us that true healing arises from the harmony of knowledge, compassion, and integrity. In every age, a physician’s first responsibility is to preserve life, relieve suffering, and act with unwavering humanity.

As medical science advances, Sun Simiao’s message continues to illuminate the path of those who dedicate their lives to healing—showing that wisdom, kindness, and moral strength remain the greatest medicines of all.

This article has been fact checked for accuracy, with information verified against reputable sources. Learn more about us and our editorial process.

Last reviewed on .

Article history

- Latest version

Reference(s)

- Aschoff, Jürgen C.. “A Physician’s View on Legal Aspects of the Contemporary Medical Use of Mercury in Germany.” Asian Medicine, vol. 8, no. 1, 17 Sep 2013, pp. 199-210. Brill, doi: 10.1163/15734218-12341276. <https://brill.com/view/journals/asme/8/1/article-p199_9.xml>.

- Zuwang, Gan. “A Critical Biography of Sun Simiao.”, Nanjing University Press, 1995, isbn: 7-305-01942-9. <http://find.nlc.cn/search/showDocDetails?docId=8357233823419590184&dataSource=ucs01>.

- Taylor, Kim. “Chinese Medicine in Early Communist China, 1945-63: A Medicine of Revolution.”, RoutledgeCurzon, 2005, isbn: 9780415345125. <https://books.google.com.pk/books?id=U6eaHe9qzcYC>.

- Unschuld, Paul U.. “Medicine in China: A History of Ideas.”, University of California Press, 1985, isbn: 9780520062160. <https://books.google.com.pk/books?id=MCXqmHj-fHIC>.

- Su, Jing. “Premodern Intercultural Communication by Reanalyzing the Phrase “Da Yi Jing Cheng (大医精诚)”.” Chinese Medicine and Culture, vol. 4, no. 1, 2021, doi: 10.4103/CMAC.CMAC_7_21. <https://journals.lww.com/cmc/fulltext/2021/01000/premodern_intercultural_communication_by.1.aspx>.

Cite this page:

- Posted by Dayyal Dungrela