Screening Tests for Infections Transmissible by Transfusion

Learn about organisms transmissible by transfusion, including viruses, bacteria, and parasites, along with preventive measures for safe blood transfusions.

The transmission of organisms via blood transfusion is often influenced by the geographical location or population where transfusion practices are prevalent. Certain organisms are more likely to be spread through transfusions in specific areas, as highlighted in the following table of transfusion-transmissible microorganisms.

|

| Prions |

|---|

| Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) and variant CJD |

| Bacteria |

|

| Parasites |

|

Global Disparities in Transfusion-Related Infection Risk

Research indicates that the risk of transmitting infections through blood transfusions is substantially higher in developing countries than in developed ones. This increased risk can be attributed to several factors:

- A higher proportion of replacement and professional donations

- Donors may conceal medical history due to social or economic pressures

- The sensitivity and specificity of screening tests may be lower

- Lack of implementation of a National Transfusion Policy

- Absence of a repeat donor system

- Donor blood collection during the window period before infections are detectable.

| Disease | Tests |

|---|---|

| Syphilis | Serologic test like Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) test |

| Hepatitis B | Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) |

| Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection | Anti-HIV 1 and anti-HIV 2 antibodies* |

| Hepatitis C | Anti-HCV antibodies |

| Malaria | Blood smear |

| * The window periods for HIV and HCV infections can be reduced through nucleic acid testing (NAT), which detects HIV RNA and HCV RNA. However, NAT is not yet mandatory. | |

Importance of Mandatory Infectious Disease Testing

Mandatory testing for infectious agents in blood transfusions is critical due to several reasons:

- Asymptomatic carriers: Many individuals infected with transmissible diseases do not exhibit symptoms.

- Extended incubation periods: Some infections, especially viral, can have prolonged incubation phases.

- Recipient safety: Preventing the transmission of blood-borne infections is vital for protecting transfusion recipients.

Characteristics of Viral Infections Transmissible via Blood

Infections caused by Hepatitis B and C, as well as HIV-1 and HIV-2, share common characteristics:

- The virus remains in circulation for an extended period without necessarily causing symptoms.

- The virus can persist in high titers.

- These infections have long incubation periods.

- Chronic carrier states can develop.

- The viruses remain viable in blood stored at 4°-6°C.

Preventative Measures Against Transfusion-Related Infections

To prevent the risk of blood transfusion-related infections, several key measures should be implemented:

- Voluntary, nonremunerated blood donation should be prioritized, excluding high-risk individuals (e.g., intravenous drug users, sex workers).

- All donated blood should undergo screening for infectious agents. Adding tests such as HIV RNA and HCV RNA can further reduce the risk.

- Universal hepatitis B vaccination should be promoted.

- Adherence to universal precautions in blood collection, processing, and storage.

- The use of leukofiltration to remove white blood cells from blood products.

- Implementation of stringent quality control measures.

Viruses

Hepatitis B Virus (HBV)

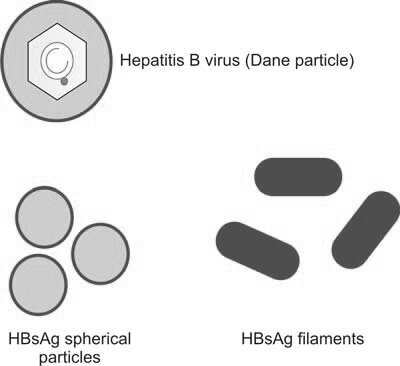

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a partially double-stranded DNA virus with a diameter of 42 nm (Figure 1). HBV can cause various clinical manifestations, including acute and chronic hepatitis, an asymptomatic carrier state, cirrhosis, or hepatocellular carcinoma.

In India, the prevalence of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) carriers is estimated between 1.5% to 4%. HBV is highly contagious and can be transmitted through all blood components and most derivatives. One Indian study reported a 6.7% incidence of post-transfusion hepatitis from a single transfusion, with a higher incidence among individuals who require frequent transfusions, such as patients with thalassemia or hemophilia. Hepatocytes infected by HBV release large amounts of HBsAg into the bloodstream, indicating active infection. HBsAg is the first serological marker of infection, appearing as early as five days post-exposure.

Screening blood donations for HBsAg has significantly decreased the risk of HBV transmission through transfusion. The common screening methods for HBsAg detection include:

- Reverse Passive Hemagglutination Assay (RPHA)

- Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

- Radioimmunoassay (RIA)

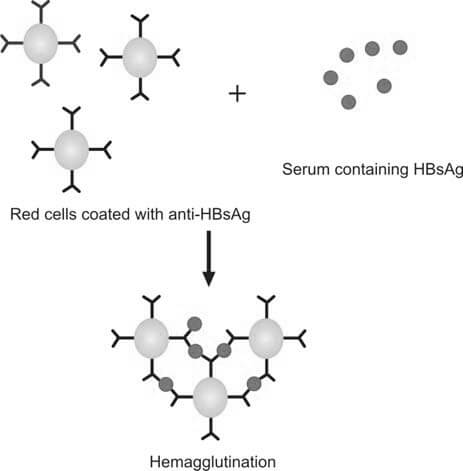

Reverse Passive Hemagglutination Assay (RPHA)

RPHA involves the addition of red blood cells coated with anti-HBs antibodies to the serum of the donor. If HBsAg is present, agglutination will occur. The test is called ‘passive reverse agglutination’ because the antibodies, not the antigen, are coated on the red cells. The test is conducted in U- or V-shaped wells of a microtiter plate and can be centrifuged to enhance agglutination. It is sensitive to 10-100 ng/mL of HBsAg (Figure 2).

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

In ELISA, the serum sample is incubated with anti-HBsAg antibodies attached to a microtiter plate. If HBsAg is present in the serum, it binds to the antibodies. An enzyme-linked anti-HBs antibody (conjugate) is then added, followed by a chromogenic substrate. If the enzyme is bound to the antigen, a color change will occur, which is measured using a spectrophotometer.

Hepatitis C Virus (HCV)

HCV is a single-stranded RNA virus from the Flaviviridae family, with an incubation period of about 8 weeks. Most individuals infected with HCV remain asymptomatic, though some may progress to chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, or hepatocellular carcinoma.

The prevalence of HCV in India is approximately 1.66%. Since HCV antigens are present in low quantities and are difficult to detect directly, screening for HCV relies on detecting anti-HCV antibodies, which become detectable 6-8 weeks after infection.

Initially, the first-generation ELISA test used recombinant proteins from the NS4 region of the HCV genome. The second-generation test improved sensitivity and specificity by incorporating antigens from both the NS3 and NS4 regions. The third-generation ELISA further enhanced detection by including antigens from the NS5 region (Figure 3).

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

HIV is a retrovirus that progressively weakens the immune system by destroying CD4+ T lymphocytes, eventually leading to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). The virus is transmitted through blood and other bodily fluids, and individuals infected with HIV are prone to opportunistic infections and malignancies (Figure 4).

In India, the prevalence of HIV is about 0.7%, with an estimated 4 million infections, primarily affecting individuals aged 15-45 years. Following infection, the virus becomes detectable in the blood within a few days, with antibodies to HIV (anti-HIV) appearing 6-12 weeks post-infection.

The window period—the time between infection and the appearance of detectable antibodies—is a critical risk period for HIV transmission through blood transfusion. HIV screening for blood donors includes testing for anti-HIV antibodies using ELISA and HIV-1 nucleic acid amplification testing (NAT), which detects viral genetic material.

After HIV infection, viremia can be detected within a few days, persisting for several weeks. The appearance of anti-HIV antibodies, a process known as seroconversion, typically occurs between 6 to 12 weeks post-infection. The ELISA method used for detecting anti-HIV antibodies is outlined in Figure 5. The window period refers to the timeframe between the initial HIV infection and the emergence of detectable anti-HIV antibodies in the blood. During this period, although the individual is infectious, the serological test for anti-HIV antibodies remains negative. Blood transfusions involving donor blood collected within this window period pose a risk of transmitting HIV to the recipient. According to the American Association of Blood Banks, whole blood donors must undergo screening tests for HIV, including (i) ELISA for anti-HIV antibodies (both HIV-1 and HIV-2), and (ii) HIV-1 nucleic acid amplification testing (NAT), with the latter relying on polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technology.

Bacteria

Treponema pallidum

Treponema pallidum, the bacterium responsible for syphilis, can be transmitted through blood transfusion. However, the risk is low, as the organism is destroyed when blood is stored at 2-8°C for 48-72 hours. Transmission is more likely through fresh blood or platelet concentrates. Screening blood for T. pallidum helps identify donors who may be at higher risk for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) (Figure 6).

The two most common tests for syphilis screening are the rapid plasma reagin (RPR) and the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) test. In the VDRL test, donor serum is heated and mixed with cardiolipin-lecithin-cholesterol antigen. A positive test results in flocculation (Figure 7).

Parasites

Plasmodium Species

The parasite responsible for malaria, Plasmodium, can be transmitted through all blood components. Diagnosis of malaria in blood donations is typically conducted through light microscopy, though this test is only positive when parasitemia exceeds 100 parasites/μL of blood.

The information on this page is peer reviewed by a qualified editorial review board member. Learn more about us and our editorial process.

Last reviewed on .

Article history

- Latest version

Reference(s)

- World Health Organization. Blood Transfusion Safety: The Clinical Use of Blood. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2002

- Dodd RY. Current risk for transfusion-transmitted infections. 2007, Current Opinion in Hematology, 14(6):671–676. Review.

- Blood Safety Indicators, 2007. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2009.

- WHO Global Database on Blood Safety, 2004–2005 report. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2008.

- Panda M, Kar K. HIV, hepatitis B and C infection status of the blood donors in a blood bank of a tertiary health care centre of Orissa. Indian Journal of Public Health, 2008; 52(1):43–44.

- Roback JD. CMV and blood transfusions. Reviews in Medical Virology, 2002, 12(4):211–219.

Cite this page:

- Posted by Dayyal Dungrela