Displaying items by tag: Diseases and Disorders

Wednesday, 26 July 2017 11:28

NUMERICAL ABNORMALITIES OF LEUKOCYTES

For meaningful interpretation, absolute count of leukocytes should be reported. These are obtained as follows:

Absolute Leukocyte Count = Leukocyte% × Total Leukocyte Count/ml

Neutrophilia:

An absolute neutrophil count greater than 7500/μl is termed as neutrophilia or neutrophilic leukocytosis.

Causes

- Acute bacterial infections: Abscess, pneumonia, meningitis, septicemia, acute rheumatic fever, urinary tract infection.

- Tissue necrosis: Burns, injury, myocardial infarction.

- Acute blood loss

- Acute hemorrhage

- Myeloproliferative disorders

- Metabolic disorders: Uremia, acidosis, gout

- Poisoning

- Malignant tumors

- Physiologic causes: Exercise, labor, pregnancy, emotional stress.

Leukemoid reaction: This refers to the presence of markedly increased total leukocyte count (>50,000/cmm) with immature cells in peripheral blood resembling leukaemia but occurring in non-leukemic disorders (see Figure 801.2). Its causes are:

- Severe bacterial infections, e.g. septicemia, pneumonia

- Severe hemorrhage

- Severe acute hemolysis

- Poisoning

- Burns

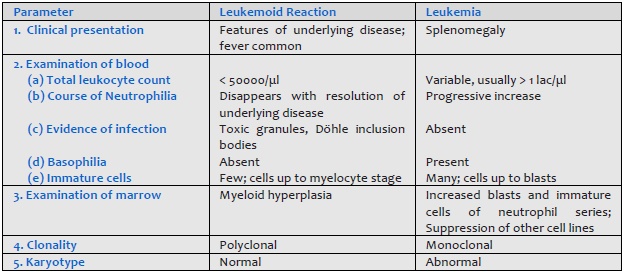

- Carcinoma metastatic to bone marrow Leukemoid reaction should be differentiated from chronic myeloid leukemia (Table 801.1).

Table 801.1 Differences between leukemoid reaction and leukemia

Figure 801.2 Leukemoid reaction in blood smear

Absolute neutrophil count less than 2000/μl is neutropenia. It is graded as mild (2000-1000/μl), moderate (1000-500/μl), and severe (< 500/μl).

Causes

I. Decreased or ineffective production in bone marrow:

- Infections

(a) Bacterial: typhoid, paratyphoid, miliary tuberculosis, septicemia

(b) Viral: influenza, measles, rubella, infectious mononucleosis, infective hepatitis.

(c) Protozoal: malaria, kala azar

(d) Overwhelming infection by any organism - Hematologic disorders: megaloblastic anemia, aplastic anemia, aleukemic leukemia, myelophthisis.

- Drugs:

(a) Idiosyncratic action: Analgesics, antibiotics, sulfonamides, phenothiazines, antithyroid drugs, anticonvulsants.

(b) Dose-related: Anticancer drugs - Ionizing radiation

- Congenital disorders: Kostman's syndrome, cyclic neutropenia, reticular dysgenesis.

II. Increased destruction in peripheral blood:

- Neonatal isoimmune neutropaenia

- Systemic lupus erythematosus

- Felty's syndrome

III. Increased sequestration in spleen:

- Hypersplenism

Eosinophilia:

This refers to absolute eosinophil count greater than 600/μl.

Causes

- Allergic diseases: Bronchial asthma, rhinitis, urticaria, drugs.

- Skin diseases: Eczema, pemphigus, dermatitis herpetiformis.

- Parasitic infection with tissue invasion: Filariasis, trichinosis, echinococcosis.

- Hematologic disorders: Chronic Myeloproliferative disorders, Hodgkin's disease, peripheral T cell lymphoma.

- Carcinoma with necrosis.

- Radiation therapy.

- Lung diseases: Loeffler's syndrome, tropical eosinophilia

- Hypereosinophilic syndrome.

Basophilia:

Increased numbers of basophils in blood (>100/μl) occurs in chronic myeloid leukemia, polycythemia vera, idiopathic myelofibrosis, basophilic leukemia, myxedema, and hypersensitivity to food or drugs.

Monocytosis:

This is an increase in the absolute monocyte count above 1000/μl.

Causes

- Infections: Tuberculosis, subacute bacterial endocarditis, malaria, kala azar.

- Recovery from neutropenia.

- Autoimmune disorders.

- Hematologic diseases: Myeloproliferative disorders, monocytic leukemia, Hodgkin's disease.

- Others: Chronic ulcerative colitis, Crohn's disease, sarcoidosis.

Lymphocytosis:

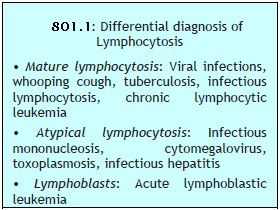

This is an increase in absolute lymphocyte count above upper limit of normal for age (4000/μl in adults, >7200/μl in adolescents, >9000/μl in children and infants) (Box 801.1).

This is an increase in absolute lymphocyte count above upper limit of normal for age (4000/μl in adults, >7200/μl in adolescents, >9000/μl in children and infants) (Box 801.1).Causes

- Infections:

(a) Viral: Acute infectious lymphocytosis, infective hepatitis, cytomegalovirus, mumps, rubella, varicella

(b) Bacterial: Pertussis, tuberculosis

(c) Protozoal: Toxoplasmosis - Hematological disorders: Acute lymphoblastic leukemia, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, multiple myeloma, lymphoma.

- Other: Serum sickness, post-vaccination, drug reactions.

Published in

Hemotology

Tagged under

Wednesday, 26 July 2017 08:33

WHITE BLOOD CELLS MORPHOLOGY

Approximate idea about total leukocyte count can be gained from the examination of the smear under high power objective (40× or 45×). A differential leukocyte count should be carried out. Abnormal appearing white cells are evaluated under oil-immersion objective.

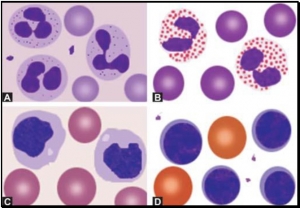

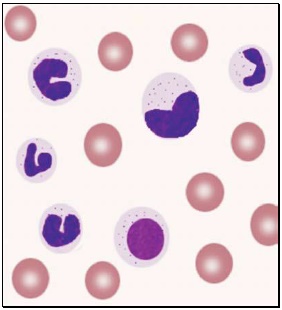

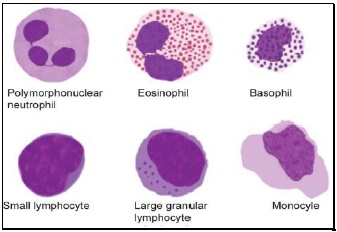

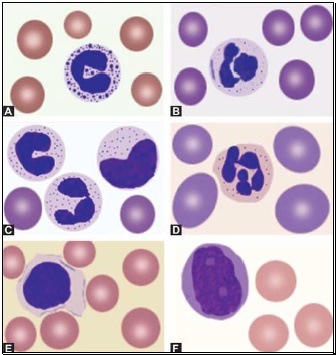

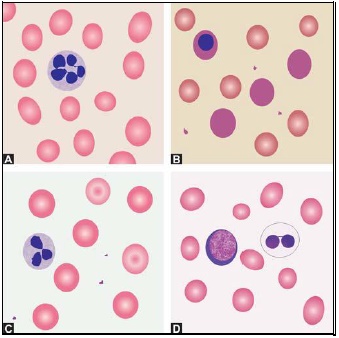

Morphology of normal leukocytes (see Figure 800.1):

- Polymorphonuclear neutrophil: Neutrophil measures 14-15 μm in size. Its cytoplasm is colorless or lightly eosinophilic and contains multiple, small, fine, mauve granules. Nucleus has 2-5 lobes that are connected by fine chromatin strands. Nuclear chromatin is condensed and stains deep purple in color. A segmented neutrophil has at least 2 lobes connected by a chromatin strand. A band neutrophil shows non-segmented U-shaped nucleus of even width. Normally band neutrophils comprise less than 3% of all leukocytes. Majority of neutrophils have 3 lobes, while less than 5% have 5 lobes. In females, 2-3% of neutrophils show a small projection (called drumstick) on the nuclear lobe. It represents one inactivated X chromosome.

- Eosinophil: Eosinophils are slightly larger than neutrophils (15-16 μm). The nucleus is often bilobed and the cytoplasm is packed with numerous, large, bright orange-red granules. On blood smears, some of the eosinophils are often ruptured.

- Basophils: Basophils are seen rarely on normal smears. They are small (9-12 μm), round to oval cells, which contain very large, coarse, deep purple granules. It is difficult to make out the nucleus since granules cover it.

- Monocytes: Monocyte is the largest of the leukocytes (15-20 μm). It is irregular in shape, with oval or clefted (kidney-shaped) nucleus and fine, delicate chromatin. Cytoplasm is abundant, bluegray with ground glass appearance and often contains fine azurophil granules and vacuoles. After migration to the tissues from blood, they are called as macrophages.

- Lymphocytes: On peripheral blood smear, two types of lymphocytes are distinguished: small and large. The majority of lymphocytes are small (7-8 μm). These cells have a high nuclearcytoplasmic ratio with a thin rim of deep blue cytoplasm. The nucleus is round or slightly clefted with coarsely clumped chromatin. Large lymphocytes (10-15 μm) have a more abundant, pale blue cytoplasm, which may contain a few azurophil granules. Nucleus is oval or round and often placed on one side of the cell.

Figure 800.1 Normal mature white blood cells in peripheral blood

Morphology of abnormal leukocytes:

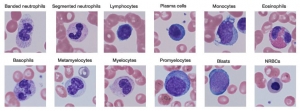

Toxic granules: These are darkly staining, bluepurple, coarse granules in the cytoplasm of neutrophils. They are commonly seen in severe bacterial infections.

Toxic granules: These are darkly staining, bluepurple, coarse granules in the cytoplasm of neutrophils. They are commonly seen in severe bacterial infections.- Döhle inclusion bodies: These are small, oval, pale blue cytoplasmic inclusions in the periphery of neutrophils. They represent remnants of ribosomes and rough endoplasmic reticulum. They are often associated with toxic granules and are seen in bacterial infections.

- Cytoplasmic vacuoles: Vacuoles in neutrophils are indicative of phagocytosis and are seen in bacterial infections.

- Shift to left of neutrophils: This refers to presence of immature cells of neutrophil series (band forms and metamyelocytes) in peripheral blood and occurs in infections and inflammatory disorders.

- Hypersegmented neutrophils: Hypersegmentation of neutrophils is said to be present when >5% of neutrophils have 5 or more lobes. They are large in size and are also called as macropolycytes. They are seen in folate or vitamin B12 deficiency and represent one of the earliest signs.

- Pelger-Huet cells: In Pelger-Huet anomaly (a benign autosomal dominant condition), there is failure of nuclear segmentation of granulocytes so that nuclei are rod-like, round, or have two segments. Such granulocytes are also observed in myeloproliferative disorders (pseudo-Pelger-Huet cells).

- Atypical lymphocytes: These are seen in viral infections, especially infectious mononucleosis. Atypical lymphocytes are large, irregularly shaped lymphocytes with abundant cytoplasm and irregular nuclei. Cytoplasm shows deep basophilia at the edges and scalloping of borders. Nuclear chromatin is less dense and occasional nucleolus may be present.

- Blast cells: These are most premature of the leukocytes. They are large (15-25 μm), round to oval cells, with high nuclear cytoplasmic ratio. Nucleus shows one or more nucleoli and nuclear chromatin is immature. These cells are seen in severe infections, infiltrative disorders, and leukemia. In leukemia and lymphoma, blood smear suggests the diagnosis or differential diagnosis and helps in ordering further tests (see Figure 800.2 and Box 800.1).

Figure 800.2 Morphological abnormalities of white blood cells: (A) Toxic granules; (B) Döhle inclusion body; (C) Shift to left in neutrophil series; (D) Hypersegmented neutrophil in megaloblastic anemia; (E) Atypical lymphocyte in infectious mononucleosis; (F) Blast cell in acute leukemia

Further Reading:

Published in

Hemotology

Tagged under

Tuesday, 25 July 2017 13:19

RED CELLS MORPHOLOGY

Red cells are best examined in an area where they are just touching one another (towards the tail of the film). Normal red cells are 7-8 μm in size, round with smooth contours, and stain deep pink at the periphery and paler in the center. Area of central pallor is about 1/3rd the diameter of the red cell. Size of a normal red cell corresponds roughly with the size of the nucleus of a small lymphocyte. Normal red cells are described as normocytic (of normal size) and normochromic (with normal staining intensity i.e. hemoglobin content).

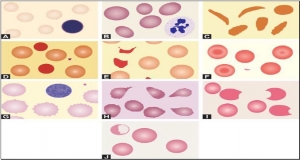

Red cells are best examined in an area where they are just touching one another (towards the tail of the film). Normal red cells are 7-8 μm in size, round with smooth contours, and stain deep pink at the periphery and paler in the center. Area of central pallor is about 1/3rd the diameter of the red cell. Size of a normal red cell corresponds roughly with the size of the nucleus of a small lymphocyte. Normal red cells are described as normocytic (of normal size) and normochromic (with normal staining intensity i.e. hemoglobin content).Morphologic abnormalities of red cells in peripheral blood smear can be grouped as follows:

- Red cells with abnormal size (see Figure 799.1)

- Red cells with abnormal staining

- Red cells with abnormal shape (see Figure 799.1)

- Red cell inclusions (see Figure 799.2)

- Immature red cells (see Figure799.3)

- Abnormal red cell arrangement(see Figure 799.4).

Red cells with abnormal size:

Mild variation in red cell size is normal. Increased variation in red cell size is called as anisocytosis. This is a feature of most anemias and is non-specific. Anisocytosis is due to the presence of microcytes, macrocytes, or both in addition to red cells of normal size.

Microcytes are red cells smaller in size than normal. They are seen when hemoglobin synthesis is defective i.e. in iron deficiency anemia, thalassemias, anemia of chronic disease, and sideroblastic anemia.

Macrocytes are red cells larger in size than normal. Oval macrocytes (macro-ovalocytes) are seen in megaloblastic anemia, myelodysplastic syndrome, and in patients being treated with cancer chemotherapy. Round macrocytes are seen in liver disease, alcoholism, and hypothyroidism.

Red cells with abnormal staining (hemoglobin content):

Staining intensity of red cells depends on hemoglobin content. Red cells with increased area of central pallor (i.e. containing less hemoglobin) are called as hypochromic. They are seen when hemoglobin synthesis is defective, i.e. in iron deficiency, thalassemias, anaemia of chronic disease, and sideroblastic anemia.

In dimorphic anemia, there are two distinct populations of red cells in the same smear. An example is presence of both normochromic and hypochromic red cells seen in sideroblastic anemia, iron deficiency anemia responding to treatment, and following blood transfusion in a patient of hypochromic anemia. In myelodysplastic syndrome, dimorphic picture results from admixture of microcytic hypochromic cells and macrocytes.

Red cells with abnormal shape:

Increased variation in red cell shape is called as poikilocytosis and is a feature of many anemias. A red cell that is abnormal in shape is called as a poikilocyte.

Sickle cells are narrow and elongated red cells with one or both ends pointed. Sickle form is assumed when a red cell containing hemoglobin S is deprived of oxygen. Sickle cells are seen in sickle cell disorders, particularly sickle cell anemia. Sickle cells are not seen on blood smear in neonates with sickle cell disease because high percentage of fetal hemoglobin in red cells prevents sickling.

Spherocytes are red cells, which are slightly smaller in size than normal, round, stain intensely, and do not have central area of pallor. The surface area of spherocytes is less as compared to the volume. They are seen in hereditary spherocytosis, autoimmune hemolytic anemia (warm antibody type), and ABO hemolytic disease of newborn.

Schistocytes are fragmented red cells, which take various forms like helmet, crescent, triangle, etc. and usually have surface projections or spicules. They are seen in microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, cardiac valve prosthesis, and severe burns.

Target cells are red cells with bull's eye appearance. These red cells show a central stained area and a peripheral stained rim with unstained cytoplasm in between. They are seen in hemoglobinopathies (e.g. thalassemias, hemoglobin disease, sickle cell disease), obstructive jaundice, and following splenectomy.disease, sickle cell disease), obstructive jaundice, and following splenectomy.

Burr cells or echinocytes are small red cells with regularly placed small projections on surface. They are seen in uremia.

Acanthocytes are red cells with irregularly spaced sharp projections of variable length on surface. They are seen in spur cell anemia of liver disease, McLeod phenotype, and following splenectomy.

Teardrop cells or dacryocytes have a tapering droplike shape. Numerous teardrop red cells are seen in myelofibrosis and myelophthisic anemia.

Blister cells or hemi ghost cells are irregularly contracted cells in which hemoglobin is contracted and condensed away from the cell membrane. This is seen in glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase defici-ency during acute hemolytic episode.

Bite cells result from removal of Heinz bodies by the pitting action of the spleen (i.e. a part of red cell is bitten off by the splenic macrophages). They are seen in glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogena-se deficiency and unstable hemoglobin disease.

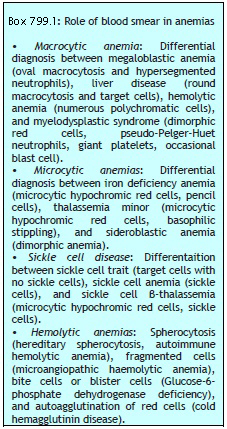

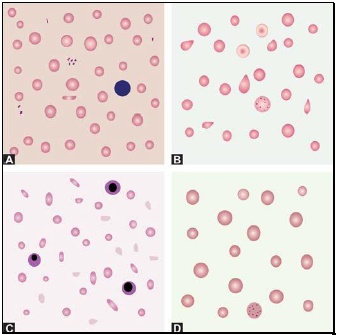

Red cell inclusions:

Those inclusions that can be visualized on Romanowsky-stained smears are basophilic stippling, Howell-Jolly bodies, Pappenheimer bodies, and Cabot's rings.

Basophilic stippling or punctate basophilia refers to the presence of numerous, irregular basophilic (purple-blue) granules which are uniformly distributed in the red cell. These granules represent aggregates of ribosomes. Their presence is indicative of impaired erythropoiesis and they are seen in thalassemias, megaloblastic anemia, heavy metal poisoning (e.g. lead), and liver disease.cell. These granules represent aggregates of ribosomes. Their presence is indicative of impaired erythropoiesis and they are seen in thalassemias, megaloblastic anemia, heavy metal poisoning (e.g. lead), and liver disease.

Figure 799.2 Red cell inclusions: (A) Basophilic stippling; (B) Howell-Jolly bodies; (C) Pappenheimer bodies; (D) Cabot’s ring

Howell-Jolly bodies are small, round, purple-staining nuclear remnants located peripherally in red cells. They are seen in megaloblastic anemia, thalasse-mias, hemolytic anemia, and following splenectomy.

Pappenheimer bodies are basophilic, small, ironcontaining granules in red cells. They give positive Perl's Prussian blue reaction. Unlike basophilic stippling, Pappenheimer bodies are few in number and are not distributed throughout the red cell. They are seen following splenectomy and in thalassemias and sideroblastic anemia.

Cabot's rings are fine, reddish-purple or red, ring-like structures. They appear like loops or figure of eight structures. They indicate impaired erythropoiesis and are seen in megaloblastic anemia and lead poisoning.

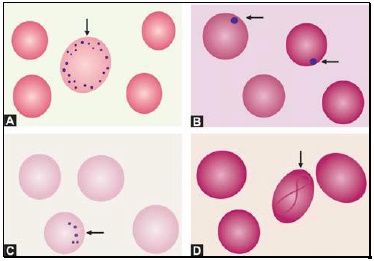

Immature red cells:

Polychromatic cells are young red cells containing remnants of ribonucleic acid. These cells are slightly larger than normal red cells and have a diffuse bluishgrey tint. (They represent reticulocytes when stained with a supravital stain like new methylene blue). Polychromasia is due to the uptake of acid stain by hemoglobin and basic stain by ribonucleic acid. Presence of polychromatic cells is indicative of active erythropoiesis and are increased in hemolytic anemia, acute blood loss, and following specific therapy for nutritional anemia.and are increased in hemolytic anemia, acute blood loss, and following specific therapy for nutritional anemia.

Nucleated red cells are red cell precursors (erythroblasts), which are released prematurely in peripheral blood from the bone marrow. They are a normal finding in cord blood of newborns. Large number of nucleated red cells in blood smear is seen in hemolytic disease of newborn, hemolytic anemia, leukemias, myelophthisic anemia, and myelofibrosis.

Figure 799.3 Immature red cells: (A) Polychromatic red cell; (B) Nucleated red cell

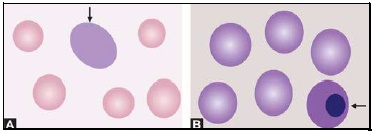

Abnormal red cell arrangement:

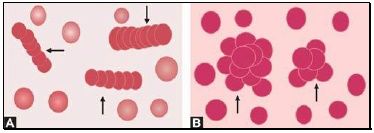

Rouleaux formation refers to alignment of red cells on top of each other like a stack of coins. It occurs in multiple myeloma, Waldenström's macroglobulinemia, hypergammaglobulinemia, and hyper fibrinogenemia.

Figure 799.4 Abnormal red cell arrangement: (A) Rouleaux formation; (B) Autoagglutination

Autoagglutination refers to the clumping of red cells in large, irregular groups on blood smear. It is seen in cold agglutinin disease. Role of blood smear in anemia is shown in Box 799.1 and Figures 799.5 to 799.7.

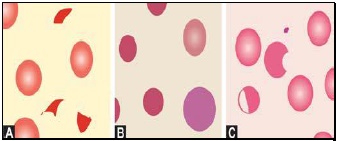

Figure 799.5 Differential diagnosis of macrocytic anemia on blood smear: (A) Megaloblastic anemia; (B) Hemolytic anemia; (C) Liver disease; (D) Myelodysplastic syndrome

Figure 799.6 Differential diagnosis of microcytic anemia on blood smear: (A) Iron deficiency anemia; (B) Thalassemia minor; (C) Thalassemia major; (D) Sideroblastic anemia

Figure 799.7 Differential diagnosis of hemolytic anemia on blood smear. (A) Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia showing fragmented red cells, (B) Hereditary spherocytosis showing spherocytes and a polychromatic red cell, and (C) Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency showing a blister cell and a bite cell

Further Reading:

Published in

Hemotology

Tagged under