Life Cycle of Malaria Parasite

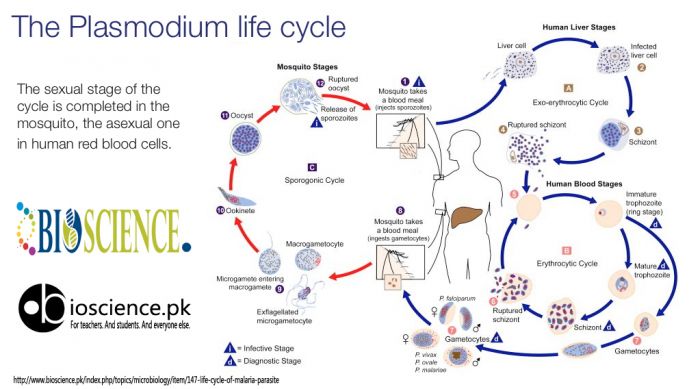

Life history of malaria parasite consists of two cycles of development: asexual cycle or schizogony that occurs in humans and sexual cycle or sporogony that occurs in mosquitoes.

Asexual cycle (human cycle, schizogony)

This occurs in the liver cells and red blood cells of infected humans, and therefore humans are the intermediate hosts of the malaria parasite (Schizogony refers to the process of reproduction in protozoa in which there is production of daughter cells by fission). The human cycle begins when infected female Anopheles mosquito bites a person and sporozoites are injected into the circulation. There are four stages of human cycle.

(a) Pre-erythrocytic schizogony (Hepatic schizogony):

Inoculated sporozoites rapidly leave the circulation to enter the liver cells where they develop into hepatic (pre-erythrocytic) schizonts (Schizonts are cells undergoing schizogony). One sporozoite produces one tissue form. Hepatic schizonts rupture to release numerous merozoites in circulation (Merozoites are daughter cells produced after schizogony). Up to 40,000 merozoites are produced in the hepatic schizont.

In P. falciparum infection, all of the hepatic schizonts mature and rupture simultaneously; dormant forms do not persist in hepatocytes. In contrast, some of the sporozoites of P. vivax and P. ovale remain dormant after entering liver cells and develop into schizonts after some delay. Such persistent forms are called as hypnozoites; they develop into schizonts at a later date and are a cause of relapse.

(b) Erythrocytic schizogony:

Merozoites released from rupture of hepatic schizonts enter the red blood cells via specific surface receptors. These merozoites become trophozoites that utilize red cell contents for their metabolism. A brown-black granular pigment (malaria pigment or hemozoin) is produced due to breakdown of hemoglobin by malaria parasites. The fully formed trophozoite develops into a schizont by multiple nuclear and cytoplasmic divisions. Mature schizonts rupture to release merozoites, red cell contents, malarial toxins, and malarial pigment. (This pigment is taken up by monocytes in peripheral blood and by macrophages of reticulo-endothelial system. In severe cases, organs which are rich in macrophages like spleen, liver, lymph nodes, and bone marrow become slate-gray or black in color due to hemozoin pigment). Rupture of red cell schizonts corresponds with clinical attack of malaria. Released merozoites infect new red cells and enter another erythrocytic schizogony cycle. This leads to rapid amplification of plasmodia in the red cells of the human host. In P. falciparum, P. vivax, and P. ovale infections, cycle of schizogony lasts for 48 hours, while in P. malarie infection it lasts for 72 hours. Merozoites of P. vivax and P. ovale preferentially invade young red cells or reticulocytes while those of P. falciparum infect red cells of all ages. Senescent red cells are preferred by P. malariae.

P. vivax, P. ovale, and P. malariae complete the erythrocyte schizogony in general circulation. Schizonts of P. falciparum induce membrane changes in red cells, which causes them to adhere to the capillary endothelial cells (cytoadherence). Therefore, in P. falciparum infection, erythrocyte schizogony is completed in capillaries of internal organs and usually only ring forms are seen in circulation.

(c) Gametogony:

After several cycles of erythrocytic schizogony, some merozoites, instead of developing into trophozoites and schizonts, transform into male and female gametocytes. These sexual forms are infective to mosquito and the person harboring them is called as a “carrier”. Gametocytes are not pathogenic for humans.

(d) Exoerythrocytic schizogony:

In P. vivax and P. ovale infections, some of the sporozoites in liver cells persist and remain dormant. These dormant forms in liver cells are called as hypnozoites. They become active and develop into schizonts a few days, months, or even years later. These schizonts rupture, release merozoites, and cause relapse. Exoerythrocytic schizogony is absent in P. falciparum infection and therefore relapse does not occur. Hence, P. vivax and P. ovale are called as relapsing plasmodia while P. falciparum and P. malariae are known as non-relapsing plasmodia.

Sexual cycle (mosquito cycle, sporogony)

The sexual cycle begins when a female Anopheles mosquito ingests mature male and female gametocytes during a blood meal. First, 4-8 microgametes are produced from one male gametocyte (microgametocyte) in the stomach of the mosquito; this is called as exflagellation. The female gametocyte (macrogametocyte) undergoes maturation to produce one macrogamete. By chemotaxis, microgametes are attracted toward the macrogamete; one of the microgametes fertilizes the macrogamete to produce a zygote. The zygote becomes motile and is called as ookinete. Ookinete penetrates the lining of the stomach and comes to lie on the outer surface of the stomach where it develops into an oocyst. On further growth and maturation, multiple sporozoites are formed within the oocyst. After complete maturation, oocyst ruptures to release sporozoites into the body cavity of the mosquito. Most of the sporozoites migrate to the salivary glands. Infection is transmitted to the humans by the bite of the mosquito through saliva when it takes a blood meal.

References

- British Committee for Standards in Hematology. The laboratory diagnosis of malaria. Clin Lab Haem 1997; 19:165-70.

- Cheesbrough M. District Laboratory Practice in Tropical Countries. 1998, Cambridge University Press.

- Chatterjee KD. Parasitology (Protozoology and Helminthology). 9th ed. Calcutta. Published by the author, 1973.

- Lewis SM, Bain BJ, Bates I. Dacie and Lewis Practical Hematology. (9th ed). London: Churchill Livingstone, 2001.

- Moody A. Rapid diagnostic tests for malaria parasites. Clin Microbiol Reviews 2002;15:66-78.

- Palmer CJ, et al. Evaluation of the OptiMal test for rapid diagnosis of P. vivax and P. falciparum malaria. J Clin microbial 1998;36:203-6.

- Warhurst DC, Williams JE. Laboratory diagnosis of malaria. J Clin Pathol 1996;49:533-98.

- Warrell DA, Gilles HM (Eds): Essential Malariology. (4th Ed). 2002. London. Arnold.

- World Health Organization. New perspectives in malaria diagnosis. World Health Organization. 2000. Geneva, Switzerland. WHO/MAL/2000.1091.

- World health Organization. Basic laboratory methods in medical parasitology. 1991. Geneva. World Health Organization.

- Comment

- Posted by Dayyal Dg.